Like in the Spanish Civil War, the “foreign legions” are complicating the resolution of the conflict in Syria.

Media reports have recently focused on the role of Iraqi Shia militias in the battle for Aleppo, essentially foreign legions fighting on behalf of the Syrian state.

Despite their differences, both the Spanish and Syrian civil wars witnessed the intervention of foreign legions, entire units of regular armies, militias, and air forces from other states, opposed to foreign fighters, independent individuals who chose to fight for an ideological cause.

In commemoration of the 80-year anniversary of the Spanish Civil War which began in July 1936, this article compares the role of foreign legions in that conflict to the Syrian civil war.

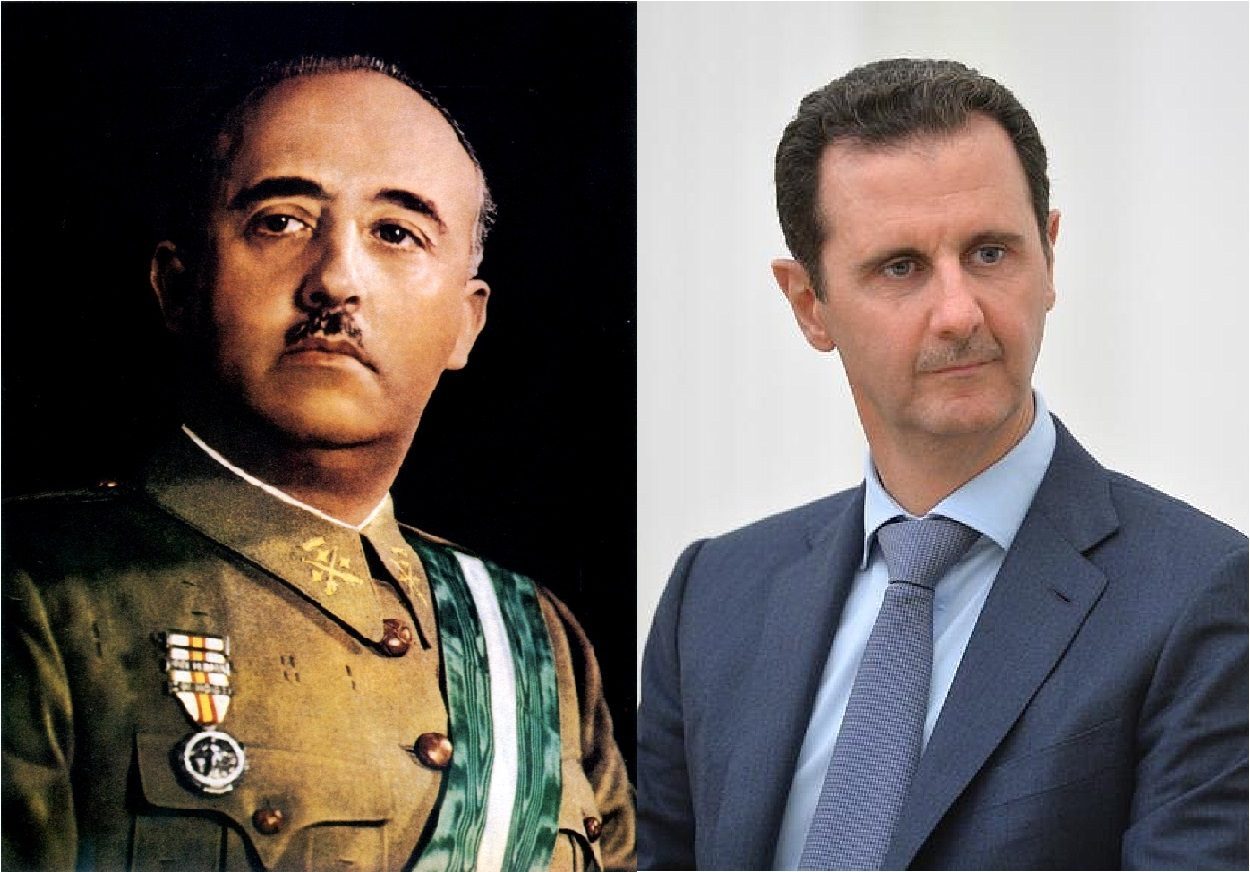

The significance of foreign legions in both conflicts is that they pushed the military momentum in favour of both Francisco Franco and Bashar al-Assad.

Assad’s dependence on foreign legions

Franco depended on foreign legions from fascist Italy, the Corpo Truppe Volontarie, Nazi Germany, the Condor Legion, and an entire contingent of Moroccans, the Regulares.

Assad’s foreign legions come from Russia, Iran, the Lebanese Hezbollah, Iraqi Shia militias, and brigades of Afghan Shia, Liwa Fatimiyyun and Pakistani Shia, Liwa Zaynibiyyun.

The question is why did Franco and Assad need these foreign legions, and what do they mean for why the Syrian civil war continues to endure?

My previous article compared the overall dynamics of both civil wars. While the Nationalists were the rebels in the Spanish Civil War, for analytical purposes I equate General Franco’s army and his faction, the Nationalists, with Bashar al-Assad and the Syrian state.

I only equate the Republican government of Spain with the Syrian rebels because of one glaring similarity. Their fighting capabilities were crippled by infighting, ultimately weakening their forces.

On the other hand, Franco and Assad’s forces did not suffer from continued military infighting, even though there were sharp political differences and rivalries in each of their coalitions.

Franco and Assad also inherited the advanced weaponry of the regular military. Yet this advantage was still insufficient to achieve an outright victory. Both needed foreign states to provide more weapons and the expertise on how to use them.

Manpower problems

Finally, both depended on foreign legions from other states owing to their manpower problems.

While the officers stayed loyal to Franco, the lower ranks defected to the Republican side, similar to the patterns of defections of the lower rank-in-file of the Syrian military to the rebels.

Franco and Assad had to replenish the rank of their militaries from their respective populations, and then later from abroad.

The population demographics of each conflict is entirely different. Spain’s population was relatively homogenous religiously, albeit with differences among religiosity among its Catholics and cultural differences among Catalans, Basques, and Castilians.

Franco could draw upon a military base in Spain that represented conservative trends, particularly strong in the north of Spain, but he would also need foreign military units to augment his ranks.

While the Syrian civil war cannot solely be attributed to just a sectarian conflict, the core military and security units the regime depends upon, such as the Republican Guard, the 4th Division, the paramilitary Shabiha (later rebranded as the National Defence Forces), do draw disproportionately upon an Alawite base.

There was a limit as to how long the Syria regime could defend itself in objective terms when the numbers of loyal fighters it can draw upon, a minority within Syria, dwindled due to attrition on the battlefield.

Assad on the offensive

There was also a limit as to how long both Franco and Assad could maintain the morale of a core of a fighters witnessing continuous combat.

Ideally, this factor works towards a resolution of civil war. Reduced manpower forces a regime to recognise that the conflict has reached a stalemate and compels them to negotiate.

With the fall of Idlib to rebel factions and Palmyra to ISIS in May 2015, the debate on the tenuous future of Syria’s regime emerged, with commentators such as Marwan Bashara asking: “Is it truly the beginning of the end for Assad and his decades’ old regime?”

The headline of a Guardian article asked, “Amid the Ruins of Syria, Is Bashar Al-Assad Now Finally Facing the End?”

An April 2015 Agence France Press article alluded to the growing rates of desertion among the Syrian military. Even Assad admitted publicly that the military had suffered setbacks after losing Idlib to the rebels and their gains outside Daraa and Qalamoun. Assad faced a stalemate at this point, and would have felt the pressure to negotiate a settlement to the Syrian civil war.

A few months later, in September 2015, the Russian air force intervened, breaking the stalemate. In this instance the decisive role of foreign air power is reminiscent of how Franco had complete control over the air, owing to the participation of the German and Italian air forces, where the infamous bombing of the Basque town of Guernica can stand in for any Syrian city today.

Combined with ramped-up support from Iran and its various foreign legions, the Syrian state was able to go back on the offensive. This is perhaps why Assad feels no need to invest in the current peace talks.

Old warriors in new conflicts

The use of foreign legions, in addition to foreign fighters, is not just a dynamic in the Syrian civil war, but in the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

The Spanish civil war demonstrates that this dynamic is not ahistorical, but common to civil wars.

The comparison I make is not to argue tat history is repeating itself, but to highlight a destructive aspect of both wars. Foreign legions have no stake in the land they fight in, as they are not connected to local communities that bear the brunt of the violence.

This disconnect between the foreign combatant and the local makes the task of resolution of the Syrian civil war that more elusive.

Ibrahim al-Marashi – Al Jazeera

The article resembles the author’s own views and doesn’t necessarily reflect MEO’s policy