As both Turkey and Iran forces themselves as essential players in the Syrian crisis, their interests seem to start contradicting and the struggle of power between the two countries became a tool for them to sideline one another.

Turkey and Iran are now on a collision course, mostly because of their involvement as the region’s major Sunni and Shiite powers in the deepening sectarian conflicts in Iraq and Syria. Their inability to accommodate each other has the potential to undermine or even undo the strong ties they have developed over the past two decades, as their economies became increasingly intertwined.

This collision became most notably after their involvement in the Syrian crisis, as Iran seeks to change the face of the country and Turkey wants to keep Syria united and strong.

Turkish military operations

Turkey’s military involvement in Syria and Iraq is partly a response to the perception that Iran is increasingly encroaching on its historic sphere of influence, especially in and around the Aleppo and Mosul battlefields close to its southern border.

In addition, the Turkish government is fighting ISIS in both Syrian and Iraq and the US-backed Kurdish militants in Syria to clear its borders of any unwanted danger.

Syrian rebels supported by the Turkish Army are currently advancing southward, having pushed the Islamic State out of the towns of Jarablous, al-Rai and Dabiq near the Turkish border between August and October. They are now at the gates of the town of al-Bab, and the stage is set for confrontation.

The strategically important city is held by the Islamic State but coveted by others: the United States-backed P.Y.D. closing in from the east, and the Syrian Army and Iranian-allied forces from the south. Already, some officials have alleged that an Iranian-made drone was involved in killing four Turkish soldiers in an air attack near al-Bab on Nov. 24.

Friction between the two countries and their proxies is rising alarmingly at a time that mutual trust has reached a nadir.

Tehran interprets Turkey’s Syria policy as primarily a product of a neo-Ottoman ambition to regain clout and empower pro-Turkey Sunnis in territories ruled by its progenitor. “What changed in Syria” after the civil war began “was neither the government’s nature nor Iran’s ties with it, but Turkish ambitions,” an Iranian national security official told me. Moreover, Iran blames Turkey for not stemming the flow of Syria-bound jihadists through Turkish territory and for giving them logistical and financial support.

Iranian goals in Syria

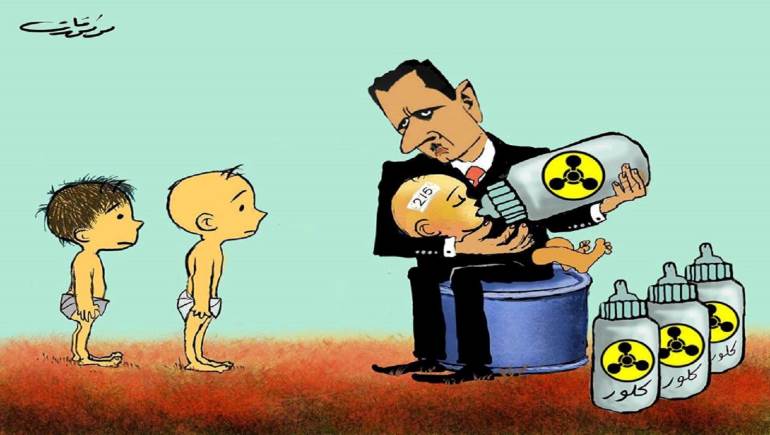

Iran also supported Assad regime by money and fighters to defend his role, in return tofreeing Iran’s hand in Syria to achieve its long-awaited dream. Iran started a demographic change in the Sunni-populated areas in Syria and sought to change the face of the Syrian cities by forcing the Shiite festivals in the heart of Damascus, adding Syria to the list of its controlled areas and making it gradually the 32nd Iranian province.

Iran has framed its war effort in sectarian terms, insisting the men it has sent to fight are in Syria to defend the shrine from “Sunni extremists”. In addresses inside Syria, Akram al-Ka’abi, the leader of the Nujaba Front, has exhorted his followers to seek revenge for battlefield losses to Sunni figures in the founding years of Islam.

The Iranian regime said that Aleppo’s fall is an important victory for their forces, and would not have been achieved without them.

“Aleppo was liberated thanks to a coalition between Iran, Syria, Russia and Lebanon’s Hezbollah,” said Yahya Rahim-Safavi, Ali Khamenei’s chief military said.

Iran is the brains behind Assad’s plan to redraw the ethnic map of central Syria. They want to evacuate all Sunnis from their areas between Damascus and the Lebanese border. Iran has brought 300 Shia families from Iraq to repopulate the Damascus suburb of Darayya, which surrendered as an opposition stronghold in August. They have also shipped in Shia families to protect the Zainab shrine. Iran’s planning is strategic, long term and deeply sectarian.

Iran pushed for an all-out offensive on Idlib after the fall of Aleppo, arguing, so far unsuccessfully, that the rebels should be given no respite.

As a result, officials in Ankara contend that Iran seeks to resuscitate the Shiite version of the ancient Persian Empire. In March 2015, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey accused Iran of fighting the Islamic State in Iraq only to replace it. Turkey also says that Iran’s mobilization of Shiite militias from Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan to protect the rule of a minority sect, the Alawites, over a majority-Sunni population in Syria has worsened sectarian tensions, giving Sunni extremists a potent recruitment tool.

Turkish-Russian alliance and sidelining Iran

After Aleppo’s defeat, Russia said its talks with the US about Syria future has ended, and it has a new plan for Syria peace talks which can be achieved with powers that have a real effect on the Syrian ground.

Russia met with Turkey and Iran and agreed to find a solution for the Syrian crisis, as Russia. However, it seemed that these three countries had different goals.

Turkey used its influence over the Syrian opposition, brought them together, and made them accept a deal with the Assad regime.

Russian president Vladimir Putin then said that both the opposition and Asad regime have signed a number of documents including a ceasefire agreement between the Syrian government and the opposition, measures to monitor the ceasefire deal and a statement on the readiness to start peace talks to settle the Syrian crisis.

Putin said that three documents which open the way to solving the Syria crisis.

Russia seemed to be not interested in annihilating the Syrian rebels, or in turning the vast majority of the Sunni Muslim population against them. The deployment of 400 Chechen military police – who are Sunni Muslims – in Aleppo was another product of the Turko-Russian pact, which was done at Turkey’s request.

Russia needs Syria as a strong country that serves as an ally in the future, and wanted no more wide military operations that exhausted its economy.

Turkey wanted to use this agreement as a tool to bring back the Syrian people together and save Syria’s demographics and integrity.at the same time, Turkey wanted to weaken Iran’s grip by pushing its backed forces back.

Turkey said that all foreign groups fighting in Syria should leave after the agreement, including the Iran-backed Shiite militias and mentioned Hezbollah’s name. Moscow informed Tehran about this clause, giving a hint that Russia is trying to weaken Iran’s presence in Syria.

Turkey also accused the Assad regime along with Hezbollah of breaching the truce and seeking to undermine the political solution.

This move angered both Iran and Hezbollah.

Ali Akbar Velayati, a key advisor to Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, said that fighters from Lebanon’s Shia Hezbollah group would not leave Syria despite a ceasefire deal.

“The claim that Hezbollah would leave Syria after the ceasefire is mere propaganda by the enemy.”

A Hezbollah official publicly declared: “We are not in Syria by Turkish decree, and we will not leave it by Turkish decree.”

The withdrawal of Hezbollah forces from Syria would have dangerous consequences, because — he claimed — it will make it difficult for Iran to prove that it is still a strong player in the region

It is not, however, the end of the story. Neither Iran nor Assad – both of whom want to press home their advantage against the rebels – will be so easily deterred, as the latest ceasefire violations around Damascus show. Having invested so much in their foreign intervention, Iran will not want to let Turkey stabilize and strengthen the Syrian Free Army under one unified command, as it now threatens to do.