BY: İBRAHIM KALIN*

BY: İBRAHIM KALIN*

The third Cultural Council served as an important venue to address the issues of Turkey’s increasingly diverse and vibrant cultural and artistic landscape.

Does culture still have a meaning in a world of what Umberco Eco calls “hyper-reality”? Answering this question is getting more difficult every day as images and simulations increasingly replace reality, and virtual realities create alternative universes. A closely linked question is how nations with long cultural traditions are to respond to the challenges of cultural impoverishment, alienation and globalization in the 21st century.

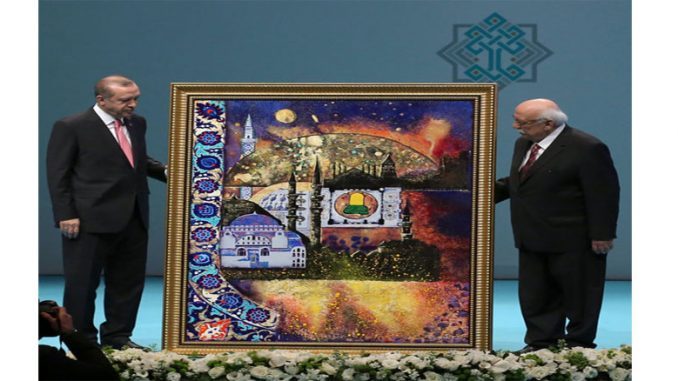

These questions were addressed at the Third National Cultural Council of Turkey on March 3-5, 2017 in Istanbul. Inaugurated by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and chaired by Culture and Tourism Minister Nabi Avci, the council brought together prominent figures and experts of the cultural and artistic landscape of present-day Turkey. The agenda was to take stock of the current state of culture in Turkey and to chart a new course for the first centennial of the Republic in 2023. Given our current post-truth, post-reality stage of modern history where “everything melts into the thin air,” this is not an easy task.

Culture — the total sum of what individuals and nations imagine, think and do to make a home for themselves in the world — is a product of local and national values. All cultures are local and national in the sense that they emerge out of a particular landscape, time and place. A given culture’s etymological and historical connection to the “soil” on which humans live, such terms as “universal culture” are somewhat misnomers. Yet, all major cultural traditions are also open to outside influences, growing and flourishing when they interact with others. As President Erdoğan noted in his speech, there does not have to be an endless war between what is local and national on the one hand, and what is considered universal and global on the other. But to do that, one needs to have an awareness of one’s own cultural values as well as a need to protect and nourish them.

The fact that a cultural product has a form that is specific to a particular nation, time and place does not prevent it from having a universal meaning. Actually, this is an important aspect of cultural and artistic expression: To create and sustain meanings and connections that overcome the barriers of time and space and to speak to people of other religious, cultural and artistic traditions.

The Euro-centric cultural imperialism in the 19th and early 20th centuries was based on a notion of cultural hegemony that deprived other nations of having culture and art in their own right. Non-Western nations were seen as backward and devoid of cultural and aesthetic taste. They had to be “cultured” and “civilized” through western invasion and indoctrination. Today, the post-colonial world has rejected much of this racist hierarchy and traditions, but variants of it remain in the veins of modern culture markets and art circles. Much of what goes around as “universal culture” is in fact western cultural products put in global currency.

The third Cultural Council served as an important venue to address these issues within the context of Turkey’s increasingly diverse and vibrant cultural and artistic landscape. Scholars, experts, artists, authors and officials searched for ways to maintain the balance between cultural change and continuity on the one hand, and the dynamic relation between what is domestic and what is global on the other. Throughout the sessions, I sensed an emerging consensus: Culture cannot be defined as absolutely complete and fixed, nor constantly changing without an anchor point and identity. Cultural traditions can live on and flourish as long as they maintain their core values and remain open to the world. One has to have roots but also keep an open horizon. As the 17th century Muslim philosopher Mulla Sadra said things possess the principle of change in their own nature (harakah al-jawhariyyah, “substantial motion”) and preserve their identity while remaining open to change. His point remains pertinent today: While focusing on change, we have to make sure to protect the substance.

The present state of Turkey’s cultural and artistic milieu displays certain features of this. Currently, there is a serious revival of traditional Islamic-Turkish arts, including: Calligraphy, ebru (paper marbling), tezhib (illumination), music, literature and architecture. The masters of these arts are producing extremely fine works and training hundreds of students across the country. There are artists that try new ways to introduce new approaches, methods and techniques into traditional art forms. There are also modern art forms that are experiencing a revival, such as: painting, novels, story writing, plastic arts, theater and cinema.

The Turkish novelist and writer Alev Alatli was right when she said at the opening panel that Turkey is going through a “cultural renaissance” today without many realizing it. The vibrancy and variety of artistic and cultural works produced in Turkey today gives significance substance to her claim.

The Council’s final reports will be immensely helpful in preparing a new roadmap for Turkey’s cultural policies. President Erdoğan said that he will establish a committee to follow up on the implementation of the outcomes and recommendations of the Council.

*Ibrahim Kalin is the spokesperson for the Turkish presidency.

(Published in Daily Sabah Turkish newspaper on Tuesday, March 07, 2017)