Amnesty International once described the Egyptian youths as “Generation Protest”, the generation who took to the streets in Egypt to bring down a dictator in 2011. But unfortunately, the Egyptian youths have now acquired a grim new nickname: “Generation Jail.”

Al-Sisi’s crackdown on the opposition far exceeds the darkest period of repression during the Mubarak era.

Human rights groups say that as many as 60,000 political prisoners now languish in Egypt’s jails. It is worth to mention that at the end of Mubarak’s rule; the figure was between 5,000 and 10,000. Egypt’s prisons are filled to triple their capacity, and the regime has built 16 more prisons to handle the overflow.

Joshua Hammer of New York Times described in his article that was titled,” How Egypt’s Activists Became Generation Jail”, how the Egyptian activists who were once dreaming of freedom, social justice and democracy, are stationed behind bars under al-Sisi’s reign.

One of them is Ahmed Maher, the leader of a social-media network of young activists called the April 6 Youth Movement. Maher mobilized hundreds of thousands of Egyptians in demonstrations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square and across the country that took down President Hosni Mubarak in January 2011.

The movement was considered for a Nobel Peace Prize, and Maher traveled across Europe and the United States talking about the Arab Spring and Egypt’s future with the likes of Ban Ki-moon and Lech Walesa.

“But the hopes that were raised by the revolution dissolved into sectarianism and chaos, and Maher’s aspirations were extinguished within two years. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the defense minister and commander in chief of the armed forces, seized power in July 2013 and outlawed protests,” said Joshua Hammer.

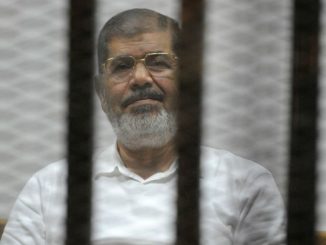

Al-Sisi carried out a bloody military coup against Egypt’s first democratically elected president Mohamed Morsi in 2013.

After five months, a judge found Maher guilty for illegal demonstration, rioting and “thuggery” and sentenced him to three years in jail. Moreover, another judge added six months to Maher’s sentence for “verbally assaulting a public officer while on duty” after he demanded that the police remove his handcuffs while in court for a 2014 appeal.

Throughout that period, Maher spent almost all his time sealed in a small cell in a solitary-confinement wing at Tora Prison, a notorious complex on the outskirts of Cairo, built during British rule, that houses about 2,500 political prisoners and common criminals.

“Hidden behind 25-foot-high walls, the vast compound encompasses seven prison blocks, ranging from a minimum-security facility for policemen and judges convicted of taking bribes to the supermax “Scorpion Prison,” a labyrinth of cells largely reserved for Islamists and April 6 leaders, “said Hammer.

After these years, Maher is now nominally a free man, but the restrictions on his movements are stifling. “The regime is deeply concerned that he could revive the social-media network that brought his followers to the streets six years ago. “

Maher said that they explained to him, “tweets can lead to demonstrations, and demonstrations can lead to revolution, and that will bring down the regime and create martyrs.” He added, “So if you are tweeting, you are like a terrorist.”

Accordingly, Maher must spend 12 of every 24 hours at his local police station every day for the next three years, “a surveillance period” intended to ensure that he refrains from anti-regime activity.

Under Egyptian law, Maher said, low-risk felons “have the right to have their surveillance inside the home with a guard downstairs. But they are using this surveillance as punishment. It is a kind of control to keep me all the time under pressure.”

Many Egyptians have accepted Sisi’s argument that another prolonged round of protests could invite radical Islamists to capitalize on the chaos.

According to Khaled Dawoud, a prominent Egyptian journalist and the leader of a small opposition party, said, “He’s positioned himself as the sole leader who makes decisions because he knows what’s best for the nation, and he’s saving us from the fate of Syria and Libya.”

However, Sisi’s crackdown has unfolded amid one of the most expansive overhauls of the legal system in Egyptian history. After declaring a state of emergency and disbanding Parliament in 2013, he issued a series of presidential decrees that granted him unprecedented power to silence his critics.

In November 2013, protest law enacted requires three days’ notification before a demonstration can take place and gives the Interior Ministry the right to “cancel, postpone or move” the protest if it determines protesters will “breach … the law.”

Broad new counterterrorism laws have expanded the definition of terrorism to include civil disobedience; this gives prosecutors latitude to roll over 15-day pretrial detention periods, in many cases without limit. And once a case gets to court, a compliant judiciary, long regarded as hostile to the opposition, has been unforgiving in its sentencing.

Joshua Hammer cited one official saying that “This is an extraordinarily conservative institution.” The official explained that judges tend to favor a “maximalist approach” to eliminate threats to the public order and safeguard their own interests.

“They are overwhelmingly the children of judges, like gondoliers in Venice. It is a family business.”

In this context, the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, a human rights group in Cairo, the minister of justice has fired almost half of the 75 judges who called for more democracy in an open letter to Sisi and replaced them with hard-liners. Two hundred others have been sidelined with administrative chores or have left the country.

One of the most notorious regime judges, Mohammed Nagy Shehata, known as the “executioner judge,” a holdover from the Mubarak era, has handed out hundreds of lengthy prison terms and death sentences to pro-democracy activists.

In early 2016, Shehata sentenced three young members of April 6, who were attending a memorial service for a murdered comrade when they were arrested, to life terms for protesting without a license, possessing fireworks and spreading false information. (The sentences were later reduced to 10 years.)

Moreover, another Cairo judge sentenced 25 peaceful demonstrators in June 2014, some of them teenagers, to 15 years for violating the protest law, blocking roads and attacking public institutions.

Dawoud said, “Kids are going to jail for four or five years,” he added, “being portrayed as anarchists and terrorists. No country in the world jails its young people for that long for demonstrating peacefully.”

During the Mubarak era, he said, “I would take part in demonstrations and spend three days in a police station. We got released because we were students, and they were not going to destroy our future. There is no more of that kind of thinking.”

In addition, a lawyer with the Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights, a nongovernmental organization that defends many protesters, Sameh Samir, said that his office has been overwhelmed by the caseload.

He said, “They are making random arrests, just sweeping people off the streets.”

He also pointed that the regime has hampered the ability of human rights groups like Samir’s to defend protesters, freezing their bank accounts and making it increasingly difficult to accept foreign funds, often a lifeline for such organizations.

“Ten and a Half Kilometers Camp, a collection of concrete bungalows surrounded by a fence just off the Cairo-to-Alexandria highway, typifies the prisons of the Sisi era. Built under Mubarak to house violent Islamists, the camp today serves as a pretrial detention facility for Islamists and a handful of secular political prisoners, “said Joshua Hammer.

In December 2015, a founding member of April 6 named Ayman, who did not want his last name mentioned, was stationed after participating in an illegal protest.

Joshua Hammer cited Ayman saying, “Thrown into a 26-foot-by-13-foot cell with 35 Islamists, he slept amid a crush of other prisoners on a blanket on the concrete floor. They defecated in a hole surrounded by curtains and were never permitted to leave the cell. “You need to take the word ‘privacy’ out of your dictionary if you are going to survive.”

Ayman was moved into a tiny disciplinary cell with 11 other prisoners to await interrogation after two weeks.

They shared a few thin blankets, drank unpurified water from a rusty pipe and survived on one piece of stale bread and cheese each day. A fluorescent light in the 10-foot ceiling shone day and night.

He said, “We learned how to get it unscrewed by standing on each other’s shoulders.” He added, “We had to use some little acrobatics.” Twice during his 26 days in the unit, he was shaken awake in the night, blindfolded, taken to an interrogation room and questioned for hours.

He said, “They asked me how the hierarchy of April 6 worked, how do we communicate,” he said. “I didn’t give them any names.” The authorities finally moved him to Al Kanatar Prison, 15 miles from Cairo, where, after 20 days, a judge ordered his release.

Ayman said that many of the prisoners he met were from the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist political organization that briefly held power after Mubarak.

Ayman said that he watched his cellmates grow hardened in prison. He said, “The torture and unjust imprisonment for long periods without clear charges or trial dates created human bombs.” He added, “Each one of them was just waiting to get out. They are so thirsty for revenge.”

In the end, Egypt’s slide back into authoritarianism in return for stability, however, al-Sisi “staked his presidency on an economic turnaround that has not materialized,” said Joshua Hammer.

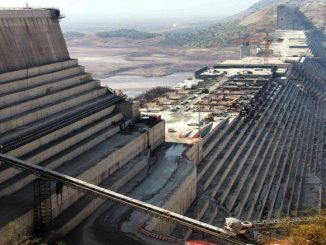

Tourism has collapsed, and the regime spent over $8 billion on a huge expansion of the Suez Canal, a money pit that depleted foreign-currency supplies and set off shortages of sugar, medicine and rice.

Moreover, al-Sisi alienated poor Egyptians by raising the price of gasoline and instituting a tax to obtain a $12 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund.

Last November, the regime devalued the Egyptian pound by 48 % to combat a black market that has siphoned almost all hard currency from the legal economy.

However,inflation rate has hiked recently after floating the Egyptian pounds.

According to a statement issued by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), the annual Inflation rate hiked to 24.3% in December, compared to 20.2% in November.

The statement attributed the increase of the inflation rate to price hikes in the food and beverage sector, as they registered an increase of 29.3%, representing a 15.12% increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)