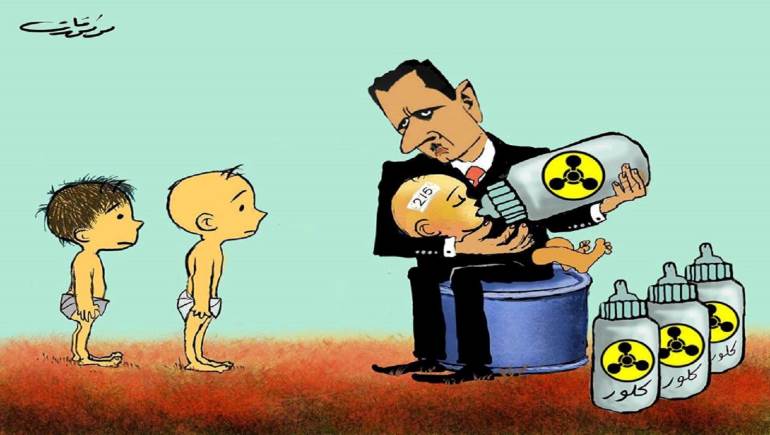

Assad regime made a deal in 2014 to surrender its chemical weapons to the international community after a deadly chemical attack in Damascus. However, facts on the ground show that the regime deceived the United Nations and is still carrying out new attacks against defenseless civilians.

Syria handed over what it said was its entire chemical arsenal to the UN’s Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in 2014 under a deal negotiated by the US and Russia after hundreds of people were killed in a sarin gas attack on the outskirts of the capital, Damascus.

The agreement averted US military strikes and the Obama administration declared one of the world’s biggest chemical weapons stockpiles “100 percent eliminated”.

And Assad insisted once again this week that the regime was not in possession of any chemical weapons.

However, there has long been suspicion – which has intensified after an attack on the rebel-held town of Khan Sheikhoun that left 86 dead – that Assad held some back.

More than 87 civilians were killed in Syria in a new chemical attack carried out by Assad regime’s air force on the rebel-held Idlib province on April 4.

Medical sources said that more than 300 other civilians were injured in this attack, and many of them were transferred to hospitals near the Turkish borders or inside Turkey, where poison tests were made.

In a sharp escalation of the U.S. military role in Syria, two U.S. warships fired dozens of cruise missiles from the eastern Mediterranean Sea at the airbase controlled by Assad regime forces from which the attack as carried out.

Trump ordered the strikes just a day after he pointed the finger at Assad for this week’s chemical attack.

“Tonight I ordered a targeted military strike on the airfield in Syria from where the chemical attack was launched.”

“Years of previous attempts at changing Assad’s behavior have all failed and failed very dramatically,” Trump said on Thursday.

Russia condemned the strikes, saying Washington’s action would “inflict major damage on US-Russia ties”, according to Russian news agencies.

Russia has also claimed the victims were killed by toxic agents released from a rebel chemical arsenal and has pushed for an international probe.

This is today in Syria in #Idlib. Hi @realdonaldtrump do you love this? pic.twitter.com/Rux9d7aV36

— Bana Alabed (@AlabedBana) April 4, 2017

Similar attack in Aleppo

In a report on February, the US-based rights group said it had verified eight chemical attacks during the offensive from November 17 to December 13, adding that four children were among the victims.

HRW said it had interviewed witnesses, collected photos and reviewed video footage to reach the conclusion that chlorine bombs were dropped from government helicopters during the operation.

Around 200 people were wounded by the toxic gasses used on opposition-controlled areas of the northern city, according to HRW.

One of the deadliest bombings hit the neighborhood of Sakhur on November 20, killing six members of the same family, including four children whose lifeless bodies were shown on a video taken by the Shabha press agency.

HRW said its report did not find proof of Russian involvement in the chemical attacks but noted Moscow’s key role in helping the government to retake eastern Aleppo.

The HRW report detailed attacks on a playground, clinics, residential streets and houses that left scores of people struggling to breathe, vomiting and unconscious.

The alleged attacks, which may have involved as many as three helicopters operating jointly, took place in areas where government forces were poised to advance, said the rights group.

“The pattern of the chlorine attacks shows that they were coordinated with the overall military strategy for retaking Aleppo, not the work of a few rogue elements,” said Ole Solvang, HRW’s deputy emergencies director.

Long history of chemical attacks

The Assad regime has repeatedly violated UN Security Council resolution 2118, which required Syria to dismantle its chemical weapons arsenal, a rights group has said in a report.

While Syrian opposition forces and human rights groups accuse the Assad regime of perpetrating the atrocity, the Syrian regime denies the claim.

Human Rights Watch said that it has strong evidence proving regime involvement in the Ghouta chemical attack.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) said it has documented 139 chemical attacks in Syria since September 2013 when the UN Security Council issued resolution 2118 for dismantling Syria’s chemical weapons arsenal.

The 10-page report notes that poison gasses were used 33 tons before Security Council Resolution 2118, adopted on 27 September 2013, while poison gasses were used in 139 attacks by both the Syrian regime and ISIS after Security Council Resolution 2118 was adopted.

The report asserts that the Syrian regime focused on its use of poison gasses on opposition-held areas where 97% of its chemical attacks targeted opposition-held areas while 3% of the attacks were carried out in ISIS-held areas.

The report sheds light on four new attacks that involved the use of chemical weapons between 1 January 2016 and 20 August 2016.

A UN investigation also concluded that Assad regime in Syria used chemical weapons against its own people.

The year-long inquiry found that the Assad regime used chlorine gas in attacks in Idlib province in 2014 and 2015.

The investigation was carried out by the Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM) of the UN and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), an international chemical weapons watchdog.

Carrying out new chemical attacks

Syria’s former chemical weapons research chief Brigadier-General Zaher al-Sakat – who served as head of chemical warfare in the powerful 5th Division of the military until he defected in 2013 – said that Assad’s regime failed to declare large amounts of sarin and its precursor chemicals.

“They [the regime] admitted only to 1,300 tons, but we knew, in reality, they had nearly double that,” said Brig Gen Sakat, who was one of the most senior figures in the country’s chemical program. “They had at least 2,000 tons. At least.”

Brig Gen Sakat believes the undisclosed stockpile includes several hundred tons of sarin and so-called precursor chemicals used to make the nerve agent, as well as aerial bombs that could be filled with chemical agents and chemical warheads for Scud missiles.

Sakat, a 53-year-old general who maintained contact with officials inside Syria after his defection in March 2013, said that in the weeks and months before the OPCW inspectors arrived the regime was busy moving its hoard.

He said tons of the chemicals were transported to the heavily fortified mountains outside Homs and to the coastal city of Jableh, near Tartus, where the Syrians and Russians have their largest military base.

Assad’s retention of chemical weapons has become something of an open secret in diplomatic circles.

Using old chemical agents

Evidence has mounted that Damascus was continuing to use chemicals – including some it had pledged to give up – in attacks on civilians. The OPCW submitted reports on the instances to the UN Security Council.

But after Russia, a veto-wielding permanent member of the council, intervened militarily in support of the Syrian government in September 2015 much of the political will to act was lost.

“There was absolutely no appetite in the UN or among member states to open that can of worms,” one senior UN official told the Wall Street Journal.

Brig Gen Sakat understands, however, that the regime has not been manufacturing more nerve agents since 2014. “They don’t need anymore, they have all they need already,” he said, speaking from a country in Europe he asked not to be disclosed to ensure his safety.

Another expert said he thought the Khan Sheikhoun attack pointed to the use of “old sarin”, or sarin that had been mixed and prepared several years ago.

“Eighty-six people were killed in the attack, which is not a lot for sarin. If you look at Halabja (the 1988 chemical attack carried out by Saddam Hussein’s forces against the Kurdish city) we think just five tons of sarin was used and more than 5,000 people died,” he said.

“Sarin degrades fairly quickly and becomes less toxic over time, so we could be looking at an attack using old sarin.”

Brig Gen Sakat believes the regime has also experimented with mixing different gasses – like sarin and tear gas – in order to create a mélange of symptoms that would make the cause hard to identify.

The Syrian government has repeatedly denied bombing Khan Sheikhoun with chemicals, saying its air strikes hit a warehouse the opposition had been using to store toxic materials.

However, British investigators with the OPCW reported on Thursday that samples from victims tested positive for sarin, a nerve agent the rebels are not known to possess.

Strategic moves

Brig Gen Sakat said it was not an accident the town was chosen for such an attack and that the regime’s use of chemicals is “always strategic”.

The northern rebel-held town links other opposition areas around Homs, Hama, and most importantly Idlib, the largest urban area under their control. “If you can take Khan Sheikhoun, or force its residents to surrender, you can take the road that connects them,” he said. And chemicals can terrify people into surrendering, he added.

He said Assad became more brazen after the US failed to act when he crossed Barack Obama’s “red line”.

“He experimented and realized everyone was silent to all his crimes: the barrel bombing of civilians and even chemical ones,” Brig Gen Sakat said. “He began acting in the face of the UN and the international community.”

He confirmed that only the head of the army, namely Assad, has the authority to order nerve gas attacks because of the potential fallout.

However, those involving chlorine and other less-deadly chemicals can be signed off by senior local commanders trusted by the regime, usually those from the same Alawite sect as the president.

Assad won’t leave its hidden chemical arsenal

In the months before he defected, Brig Gen Sakat said he was personally ordered by his commander, Gen Ali Hassan Amar, to carry out three chemical attacks.

They took place in October 2012 in the southern town of Sheikh Maskeen, in December 2012 on nearby Harak, and in January 2013 on Busra al-Hariri – all places where demonstrations had been taking place against Assad.

He was told the people “needed to be reorientated”, but Brig Gen Sakat knew the intended target was civilians supportive of the rebellion.

He was told to prepare phosgene, which at high concentrations damages the lungs within seconds and causes death by suffocation. But under the cover of darkness, he switched it for water and diluted bleach which would cause no real harm.

But the attacks were claiming few victims and after the third time, the regime became suspicious. It was then he decided to escape to Jordan and then on to Turkey, where he joined the opposition Free Syrian Army.

“I couldn’t believe at the beginning that Assad would use these weapons on his people,” he said.

Syria’s chemical weapons program was started in the early 1980s with the aim of defending against enemy states such as its neighbor, Israel. “I could not stand and watch the genocide. I couldn’t hurt my own people,” he said.

Brig Gen Sakat has had several attempts on his life since defecting and has given few interviews since leaving Syria.

He now works documenting chemical attacks from outside the country, sharing evidence and information from local activists with the OPCW.

He said he does not think Assad will give up the remaining stockpile as long as he is in power.

“He will not let go of the chemical weapons while he is the leader of Syria,” the general said. “If he is forced to leave, he might confess to where some of it is hidden only so it doesn’t end up in the wrong hands.”

The Syrian crisis began as a peaceful demonstration against the injustice in Syria. Assad regime used to fire power and violence against the civilians and led to armed resistance. 450.000 Syrians lost their lives in the past five years according to UN estimates, and more than 12 million have lost their homes.