With the first phase of the new four-towns evacuation deal in Syria finally over, Assad regime was able one more time to use the Syrians’ dreams and struggle for freedom against them to fulfill its long-awaited goal in changing Syria’s demographics and stabilize its role even more.

Assad regime forces, helped by Russian air power and Iran-backed Shiite militias, has steadily since 2014 ended armed opposition influence in many parts of Syria by forcing the rebels to accept withdrawal deals after long periods of siege, bombing, and starvation.

The deals which are described as reconciliation agreements were made to a number of besieged areas, mainly aiming at allowing armed opposition fighters to leave government-besieged cities and town to opposition-held areas in northern Syria, near the borders with Turkey.

These deals also offer civilians the opportunity to flee conflict zones and allow entry of humanitarian aid into war-afflicted areas. International actors involved in the Syrian conflict such as Russia, Iran, and Turkey have been acting as mediators.

Assad regime describes the evacuation deals as “reconciliation” or “settlement agreements”, but rebels say they involve the forcible displacement of whole communities from opposition areas aiming at reshaping the demographic population structure of the country.

“The compulsory deportation agreement in Al Waer neighbourhood in Homs came to announce the forceful entrance of the Russians in line with the [regime’s] demographic change plans targeting all those who are regarded by the Syrian regime as part of a ‘useful Syria’, under the patronage of Russia,” wrote Syrian activist and writer Omar Kokash in reference to the recent swap deal carried out on April 8 in Al Waer neighbourhood, the last opposition-held district in Homs.

The four-towns agreement between the rebels and the regime was the last episode of these deals, which started in 2014 with the Homs evacuation deal.

Homs, February 2014

An agreement was reached between the Syrian regime and the United Nations on the evacuation of Syrian civilians from Homs and the entry of humanitarian aid into the city.

The rebel-held Old Homs districts in the center of the city have been under tight siege by Assad’s troops since June 2012.

Yarmouk, December 2015

The Syrian Human Rights Observatory reported that the Islamic State (ISIS) and the Syrian regime had reached an agreement to facilitate the departure of ISIL fighters and their families from southern Damascus neighborhoods, including the al-Yarmouk, the Palestinian refugees camp.

The agreement was discreetly reached between the regime and ISIS through local and international mediation. It stated that the evacuees would be transferred to Beer Qassab town in Damascus’s southeastern countryside, Homs’s eastern countryside or Raqqa city.

Qamishli City, April 2016

An agreement was reached between the Syrian regime and the Kurdish People’s Protection Units in Qamishli city. The agreement stated the following:

• Exchange of prisoners between the two parties.

• Upholding a ceasefire in the city.

• Discussing locations of posts where government forces and pro-government militias would be deployed and others where Kurdish forces would be deployed.

• All Kurds held prisoners by the government in Qamishli since before 2011 must be released.

• The regime will not arrest any Kurd for any reason nor will it arrest any Arab or Christian affiliated with the Kurdish People’s Protection Units or working with the Kurdish administration.

Daraya, August 2016

An agreement reached between the Syrian regime and opposition allowed civilians and armed opposition fighters to leave Daraya town in Damascus’s countryside. The agreement stated the following:

• Civilians leave Daraya and head to regime-controlled areas in Sahnaya town, in Damascus’s countryside.

• Armed fighters leave Daraya and head to Idlib, in northern Syria.

• The agreement is implemented under the supervision of the International Committee of the Red Crescent.

Al Waer, September 2016

” Al Waer Agreement ” between the Syrian regime and the opposition under the patronage of the United Nations. The agreement stated the following:

• The regime halts the bombing of Al Waer neighborhood in Homs.

• Opposition fighters are allowed to leave the neighborhood, in separate groups, and head towards northern Syria, as follows:

1. Three hundred fighters leave with their families from Al Waer to opposition-held areas in Idlib, and in return, the regime opens all roads leading to the neighborhood and allows entry of food supplies to the area.

2. The regime releases 200 Al Waer residents held in jail, and in return, 500 opposition armed fighters and their families will leave the neighborhood and head towards Idlib.

3. The regime reveals information about prisoners held in jail, and in return, 300 opposition armed fighters leave with their families.

4. The opposition withdraws from government sites and posts in the neighborhood as the rest of the armed fighters leave with their families.

5. The Syrian regime is handed over full control over the neighborhood.

Moadamiyah, October 2016

Hundreds of armed opposition fighters and their families left on October 19, 2016, the Damascus suburb of Moadamiyah heading towards Idlib, in northern Syria.

Up to 3,000 people were set to leave Moadamiyah as part of this deal between the Syrian regime and the opposition, including 620 armed fighters, their families and people from Daraya and Kafr Sousa who had been living in Moadamiyah after fleeing their homes.

In the same month, an agreement between the Syrian regime and opposition was reached on the departure of 600 opposition fighters with their families from Qudssaya and al-Hama towns in Damascus’s countryside. The agreement, effective starting from October 11, stated the following:

• Five hundred opposition fighters and their families leave Qudssaya and head towards Idlib.

• One hundred opposition fighters and their families leave Hama and head towards Idlib.

• The fighters must hand in their weapons.

• Opposition fighters who choose to stay in the towns will hand in their arms and get their situation settled by the regime.

• The regime lifts the blockade imposed on civilians in the two towns.

• The regime restores water and electricity services in the two towns.

Al Tal, November 2016

An agreement reached between the Syrian regime and the opposition in Al-Tal town in Damascus’s countryside. The agreement stated the following:

• The opposition hands over Al-Tal town to the regime.

• The regime allows opposition fighters, armed with light weapons, to leave Al-Tal and head towards Idlib.

Khan al-Sheeh, November 2016

An agreement reached between the Syrian regime and the opposition groups to evacuate all the opposition’s armed fighters from the Palestinian refugee camp of Khan al-Sheeh in Damascus’s countryside to opposition-held areas in Idlib.

The agreement stated that opposition fighters could keep their light arms but must hand in their medium and heavy arms in return for ending the regime’s shelling on the refugee camp, lifting the siege, allowing entry of humanitarian aid and restoring all public services in the camp.

East Aleppo, December 2016

An agreement reached between the Syrian regime and the opposition on the evacuation of civilians and opposition armed fighters from east Aleppo, to head towards Aleppo’s northern and western countryside.

Aleppo, December 2016

An agreement between the Syrian armed opposition, including Ahrar al-Sham, on one side, and the Syrian regime and Russia, on the other, to allow the evacuation of civilians from Aleppo. The agreement stated the following:

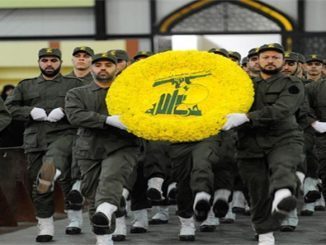

• Full evacuation of Aleppo civilians in return for the evacuation of a set number of “people” from Kefraya and Foua, in Idlib’s countryside, two towns besieged by the opposition’s “Jaish al-Fatah”, and others from Madaya and Zabadani, in Damascus’s countryside, that are besieged by the pro-regime Hezbollah forces.

Wadi Barada, January 2017

“Wadi Barada” agreement signed between the Syrian regime and the opposition through the mediation of a German delegation. The agreement stated the following:

• A ceasefire between the two parties in Wadi Barada region.

• Armed opposition to leave Ain al-Fijeh town and head towards Deir Muqaran village.

• Armed opposition fighters and civilians who choose to remain in Wadi Barada must reach reconciliation with the regime and get their situation settled by the regime. Otherwise, they must leave to Idlib.

• The return of families of opposition fighters who had previously fled from Wadi Barada so they can escort the fighters (their relatives) as they head towards Idlib.

Four Towns agreement, April 2017

The “Four Towns” agreement between the Syrian opposition’s “Tahrir al-Sham” and “Ahrar al-Sham”, on one side, and the Syrian government, the Lebanese Hezbollah and the Iranian side, on the other.

The agreement stated the following:

• Up to 3,800 people, including opposition fighters, to leave from Zabadani, in Damascus’s countryside, and head towards Idlib.

• Up to 8,000 people, including pro-regime militiamen, to leave from Kefraya and Foua, in Idlib’s countryside, and head towards Aleppo.

• Exchange of prisoners and dead bodies.

• The departure of those who want to leave Madaya, Zabadani, and Bloudan towards the north.

• The release of 1,500 prisoners held by the Syrian government, mostly women.

• Resolving the case of 50 families, originally from Zabadani and Madaya, stuck in Lebanon in return for the departure of all of Kefraya and Foua’s residents in two groups.

The clear sectarian basis of the four-towns deal

Madaya and Zabadani, once summer resorts to Damascus, have been shattered under the cruelty of government siege. The two towns rebelled against Damascus’ authority in 2011 when demonstrations swept through the country demanding the end of President Bashar Assad’s rule.

Residents were reduced to hunting rodents and eating the leaves off trees. Photos of children gaunt with hunger shocked the world and gave new urgency to U.N. relief operations in Syria.

Foua and Kefraya, besieged by the rebels, lived under a steady hail of rockets and mortars. However, they were supplied with food and medical supplies through military airdrops.

In a video posted on Facebook from one of the buses departing Madaya, a man identified as Hossam said: “We were forced to leave. We left our land, our parents, our memories, our childhood — everything.”

Critics say the string of evacuations, which could see some 30,000 people moved across battle lines over the next 60 days, amounts to forced displacement along political and sectarian lines. The United Nations is not supervising the evacuations.

The predominantly Shiite towns of Foua and Kefraya have remained loyal to the Syrian government while surrounding Idlib province has come under hard-line Sunni rebel rule. Their populations will now find security under the government’s outwardly secular authority.

Madaya and Zabadani, on the other hand, are believed to now be wholly inhabited by Sunnis, the consequence of six years of deft political maneuvering by Assad to steer what started as a broad movement against his authority into a choice between him and Sunni Islamist rule.

“They, of course, wanted to beat the Sunni rebels into submission,” said Joshua Landis, director of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma. “This has had the effect of driving them out.”

Uprooting the original citizens

Since 2011, 5 million Syrians have been made refugees and another 7 million have been displaced within the country’s borders.

“The amount of population rearrangement has been tremendous in Syria,” said Landis. The latest evacuations are “a drop in the bucket.”

Of the estimated 40,000 inhabitants of Madaya, some 2,000 elected to take the buses to rebel-held Idlib province rather than be subjected to the notorious government security services. They include former fighters, activists and medical workers, who have been targeted by the government with detention, torture and bombardment throughout the conflict.

“Honestly, when we left Madaya, I felt sadness, anger, and sorrow. But now, on the road, I don’t feel anything. I feel cold as ice,” said Muhammad Darwish, a 27-year-old medical worker.

Zabadani, however, is to be depopulated. The town’s last 160 holdouts — all believed to be fighters or medical workers— will evacuate to Idlib on Saturday.

The Assad regime maintains it is offering its opponents amnesty and the right to stay in their homes, but its brutal military campaigns have already pushed tens of thousands of people into Idlib and Aleppo provinces.

In the last year alone, the regime has uprooted residents and gunmen from the towns of Moadamiyeh, Hameh, Qudsaya, Darayya and the Barada Valley around the capital, as well as once rebellious neighborhoods of Aleppo and Homs, Syria’s largest and third-largest cities, respectively.

Most of eastern Aleppo was depopulated through force, as well. A U.N. inquiry said the evacuation of east Aleppo amounted to a war crime because it was coerced through the joint Russian and Syrian government campaign against the city’s civilian infrastructure. More than 20,000 people were bused out of Aleppo at the end of last year, to rebel-held provinces in the northwest.

U.N. Syria humanitarian adviser Jan Egeland said there had been more evacuation deals this year than before, but that they appeared driven more by military priorities than humanitarian concerns.

“They seem to follow a military logic, they do not seem to put the civilians at the heart of the agreement,” he told reporters in Geneva on Thursday.

The United Nations was not involved in the evacuation of the four towns. Egeland said that it was misleading to consider them voluntary evacuations when the towns had been besieged for years.

“Besiegement should end by being lifted,” he said, “not by places being emptied from people.”