The Trump administration is wisely designating affiliates as terrorists, but not the umbrella organization, says a recent Bloomberg report.

A year ago it looked like Donald Trump was going to designate the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. Some of his closest advisers pushed for it. U.S. allies like Egypt quietly made the case too. Many Republicans in Congress also believed the movement that created political Islam should be treated like al Qaeda.

It didn’t happen. Trump administration officials tell me the initial proposal last year to designate the entire Muslim Brotherhood, which includes chapters and offshoots in countries all over the world, stalled out. By the time the White House approved its national security strategy in December, it didn’t even mention the Muslim Brotherhood by name.

Instead the Trump administration has settled on a more refined approach, seeking to designate violent chapters of the Muslim Brotherhood as terrorists, but not going after the entire organization. As the national security adviser, H.R. McMaster, told reporters in December: “We will be evaluating each organization on its own terms. The organization is not monolithic or homogenous.”

In some ways this approach is not new. The Obama administration managed to reach out to the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt after the Arab Spring in 2011, and nonetheless treat its Palestinian wing, Hamas, as terrorists. There are no plans for the Trump administration to attempt to find common ground with the Muslim Brotherhood, U.S. officials tell me. But the administration is getting more aggressive against the Brotherhood’s violent affiliates.

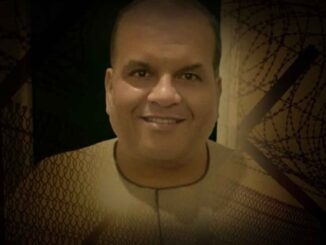

On Wednesday, the U.S. ambassador for counterterrorism, Nathan Sales, gave some specifics on this new approach at the annual conference for the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv. To start he named Ismail Haniyeh, the chief of the Hamas politburo, as a specially designated global terrorist. That means his assets will be blacklisted from the global financial system. Hamas was first designated as a terrorist organization by the U.S. government in 1997. But in Obama’s second term, the pace of designations against Hamas slowed to a trickle.

Jonathan Schanzer, the senior vice president for the Foundation for Defense of Democracies told me this week, “There was a reluctance in the last three years of the Obama administration to designate Hamas guys.” Part of this is because of Israel. After the 2014 rocket war with Hamas in Gaza, Israel reached an understanding with two principal supporters of Hamas — Qatar and Turkey — to allow more approved goods into Gaza, loosening the blockade Israel imposed after 2007 when Hamas took over Gaza and ousted the Palestinian Authority. Schanzer told me that at the time, he had heard from his contacts at the Treasury Department that they did not want additional sanctions to undermine those nations’ understanding with Israel.

“It’s interesting that the U.S. is signaling it does not see a difference between the political leadership in Gaza, the politburo and the military leadership,” Schanzer said. This approach is evident in the State Department’s announcement of the new designation for Haniyeh. It says: “Haniyeh has reportedly been involved in terrorist attacks against Israeli citizens. Hamas has been responsible for an estimated 17 American lives killed in terrorist attacks.”

Another reason the Haniyeh designation is important is because it signals the U.S. will not support efforts at a reconciliation between Hamas and Fatah, the party of the Palestinian Authority president, Mahmoud Abbas. Trump has already threatened to cut off aid to the statelet Abbas runs, and Abbas responded in January with a deranged speech declaring the peace process a dead letter. Now Sales is making clear the U.S. will not encourage a Palestinian unity government either.

Sales also announced the designations of two relatively new organizations, Liwa al Thawra and Harakat Sawa’d Misr. The groups, formed in 2016 and 2015, are led by former members of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. Both groups have taken responsibility for acts of terror.

Operatives for Liwa al Thawra last year claimed responsibility for a bombing outside of an Egyptian police training facility. In 2016, the group was responsible for the assassination of Brigadier General Adel Ragai, who commanded the Egypt’s Ninth Armored Division.

Harakat Sawa’d Misr also has a violent past. It attempted the assassination of Egypt’s former Grand Mufti Ali Gomaa, and killed Ibrahim Azzazy, an officer with Egypt’s National Security Agency. In 2017, the group claimed responsibility for an attack on the Egyptian embassy in Myanmar.

Egypt’s president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, has pressed the U.S. to designate the entire Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. He will likely view these designations as a half measure. But of course, Egypt’s government, which has expanded its domestic crackdown well beyond the Muslim Brotherhood, does not dictate U.S. policy.

America must draw a distinction between nonviolent Islamists and those who turn to terror. The designations announced Wednesday are important in this respect. But it’s no substitute for a coherent policy on the Muslim Brotherhood. For that the Trump administration must devise a strategy for countering, engaging or ignoring groups that seek to impose Islamic rule through the ballot and not the bullet.