Banners line streets of Cairo telling citizens to vote to extend presidency of Abdel Fatah al-Sisi

Polling stations across Cairo filled with people as Egyptians voted in a snap referendum expected to allow President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi to remain in power until 2030. Six people said that they had been bussed to the polls from working-class areas, and given bags of food in exchange for their vote.

Amid a subdued atmosphere on the streets of downtown Cairo, banners lined the streets telling citizens to vote to confirm the changes. A lone banner from the Egyptian Conservative party hung above one central square, stating that it “rejected the constitutional amendments,” which also increased Sisi’s control over the judiciary and expanded the military’s role in politics.

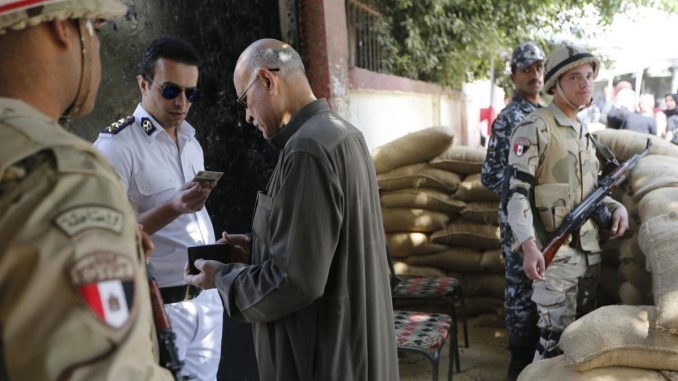

Gun-toting soldiers and members of the security services watched over polling stations, accompanied by teenagers wearing T-shirts bearing the logo of the “do the right thing” campaign, set up to encourage citizens to vote, often in favor of the changes. The campaign’s logo was visible on dozens of microbuses lining the streets around polling stations in central Cairo, where voters said the buses had brought them from working-class neighborhoods surrounding the capital. A recent change to election regulations allowed Egyptians to vote anywhere in the country, not just their local area.

The amendments are predicted to pass, allowing Sisi to extend his current term until 2024, with a third term lasting until 2030. The vote, some observers believe, marks the end of the constitutional guarantee that Egyptian presidents may only rule for two terms, the last remaining achievement of the 2011 uprising that toppled former autocrat Hosni Mubarak.

The sweeping changes will also create a second house of parliament, the role of vice-president and add a 25% quota for women.

“All the polling stations are full like this,” said Amal Ali, as she stood in front of a polling station in downtown Cairo. Her husband, she said, was one of the microbus drivers who had brought people from the Giza neighborhood of Talbiya, and had returned to collect more. “Two or three people on every bus will vote no,” she said, but was unable to point out anyone she knew who had done so.

A group of four women sat inside a nearby microbus bearing the “do the right thing” logo explained the bus had brought them to the polls from Qalyubia, south of Cairo. All declined to give their names, for their own safety. “Ten days before the vote, someone said if you show your ink-stained finger, you’ll get a bag worth 150LE [£6.70],” one explained. All four women said they had voted in favor of the amendments.

“Imagine how poor we are that we came all this way to sell our vote,” said another. “Everything now is hard – if someone has five kids they have to beg in the street,” she said, in reference to harsh austerity measures. “Some people can’t afford food or clothing. If they arrest me, I don’t care.”

A third woman complained that the bag of food they had been promised by the driver “would be big – but it’s small”.

“With us he will win. Without us, he will also win,” said a fourth woman, in reference to Sisi.

Around the corner, close to Cairo’s Tahrir Square, which formed the central point of the 2011 uprising, a group of 10 people jostled in front of a microbus. “Some people took more than two bags, so they’re fighting,” explained a woman standing nearby, who had travelled with the group. “Now they’re refusing to go back until they’ve got their share.” Nearby, others carried armfuls of black plastic bags of food.

The driver of the van, who did not give his name, explained that the small bags contained cooking oil, salsa, pasta, rice and sugar. “Some guy at the bus stop gave us the bags,” he said.

The campaign to demand that citizens vote in favor of the changes began long before a referendum was officially declared, when 531 out of 596 MPs supported the amendments just four days before the vote. Most people said they had learned about the referendum from television and newspaper reports in the pro-government media. Very few said they were aware of any campaign to demand that citizens vote against the reforms.

“We were not given any chance to campaign,” said Khaled Dawoud, a longtime opposition figure and a member of the Civil Democratic Movement set up to oppose the changes. “Our members were arrested, and we had no access to local media at all.”

With days between the declaration of a referendum and the vote, international observers were unable to organize themselves to oversee the polling. “That’s their problem,” said a judge as he watched over a polling center in downtown Cairo. “Most people following the referendum knew it would happen now.”

As mass protests rose up against military dictatorships in Sudan and Algeria, banners appeared on the streets of Cairo telling Egyptians that Sisi’s rule was a guarantee of future stability and prosperity. The former minister of defence who swept to power in a coup in 2013 renewed his current mandate in 2018 with 97.8% of the vote.

“You see what’s happening in the Arab world right now? Look at Syria, or Iraq. Egypt wants to avoid what happened in other countries,” said Mahmoud Hamma, who said he had voted in favor of the reforms.

Others were determined to vote against the changes, despite the odds. “I will go and vote no because this man and this government should not continue. Everything is now worse,” said Mohammed, a parking attendant who spoke by telephone from Luxor, and whose surname has been withheld for his safety. “I even voted for Sisi in the first elections in 2014, and I am regretting this now,” he said.