Egypt’s strongman repeats Hosni Mubarak’s errors, to everyone’s peril.

Several years ago, in Cairo, I asked Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to name Hosni Mubarak’s biggest mistake. “He stayed in power for a long time,” Egypt’s sixth president said of its fourth, who ruled like a pharaoh for nearly 30 years before being toppled in the heady early days of the (mislabeled) Arab Spring.

Since then, el-Sisi, who took power in a 2013 military takeover, was “re-elected” to a new term with 97 percent of the vote, and has amended the Constitution to potentially stay in power until 2030. He seems to imagine he’s popular.

On Thursday I was invited to join a group of about 25 people to meet el-Sisi at New York’s Palace Hotel, where he was staying for his visit to the U.N. General Assembly. The meeting was held under the Chatham House Rule, which prevents me from quoting anything that was said — except that el-Sisi went on the record to invite me to tour some new construction in Egypt that he asked me not to describe as palaces. (I accepted.)

“Where will I receive President Trump?” he says of the man who calls him his “favorite dictator,” adding that the cost of these nonpalaces is “nominal” and that their style needs to be “suitable.”

Whatever the buildings are supposed to be called, el-Sisi has embarked on a building spree involving a $58 billion new administrative capital along with 13 additional new cities, even as he’s otherwise followed a standard I.M.F.-driven austerity program that has badly squeezed ordinary Egyptians.

But the Ozymandian ambitions have run up against funding problems, with the United Arab Emirates no longer so keen to foot the bills for the new Luxors.

They’ve also run up against political problems. Protests across the country this month triggered by a building contractor’s allegations of lavish excess and mishandling of funds, have underscored the breadth of dissatisfaction with el-Sisi’s rule. The regime has responded with a fresh wave of arrests that number in the thousands and a flood of police and security forces in Cairo’s Tahrir Square — underscoring el-Sisi’s fears that what was done to Mubarak may be done to him.

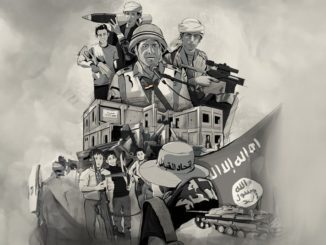

That’s not likely to happen, yet. Egyptians don’t want to see their country become another Syria, Libya or Yemen, where revolt led to apocalypse. Nor are most Egyptians keen to return to the sort of democracy they briefly had under the leadership of Mohamed Morsi, the Muslim Brother whose short reign was heading toward dictatorship before el-Sisi overthrew and arrested him. He died of a heart attack while on trial on espionage charges.

But does that mean that el-Sisi’s warmed-over Mubarakism — dictatorship without fanaticism; institutional corruption without outright plunder; a security state without mass murder; cooperation with the West in international affairs without the adoption of Western political values — is the best Egypt can hope for?

I used to think so. Democracy turned out to be an invitation to Islamism. Egyptian liberalism, sometimes inflected with anti-Semitism, has never drawn majority political support. El-Sisi has been determined to preserve his ties with the U.S. and Israel and fight terrorists militarily and ideologically.

As for the other major alternatives offered by Arab political leaders, they boil down to secular dictatorships on the Algerian model, military dictatorships on the Sudanese one, familial dictatorships on the Saudi one or Islamist dictatorships on the Gazan one. Tunisia, sometimes touted as the Arab Spring’s success story, sits on a political knife’s edge.

Is Egypt really so bad by comparison?

It may turn out to be worse. El-Sisi squandered the historic opportunity to set the example of leaving office voluntarily, as Nelson Mandela did, even if he did so in the context of a managed transition to a trusted lieutenant in his own party (akin to Mexico under the old ruling P.R.I. party or South Africa under the A.N.C.). El-Sisi lost his chance to at least diminish the overwhelming role the military plays in the Egyptian economy, opening it to new players and defusing a major source of popular resentment. And he needlessly burned bridges with liberals, Egyptian and Western, by treating them as political enemies nearly on a par with the Muslim Brotherhood.

The upshot is that he’s made any kind of gradual but effective political, economic and ideological reform all but impossible. He wants to present Egyptians with a binary choice: him, or the deluge. Eventually, but inevitably, the deluge wins.

Favorite dictator or not, el-Sisi is not going to be a good long-term bet for the United States — and, like the late shah of Iran, could wind up being a disastrous one. That’s not an argument for this administration, or the next, to cut him off. It is an argument for saying there ought to be a price for American support, paid in the coin of gradual political and economic reform.

El-Sisi, of all people, should know this. “We are not gods on earth,” he told me when we met a few years ago in Cairo. His interest in self-preservation, to say nothing of the good of Egypt, should prompt him to stop acting as one.

BY: Bret L. Stephens, an Opinion columnist with The Times since April 2017. He won a Pulitzer Prize for commentary at The Wall Street Journal in 2013. The article was published in The New York Times on 27 Sept. 2019.