A prominent German philosopher reverses earlier decision to accept Sheikh Zayed Book Award over its over human rights concerns.

German philosopher Jurgen Habermas has rejected a literary award by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Sunday due to the Gulf country’s downward human rights record.

Juergen Habermas, a well-known sociologist and commentator, announced on Sunday that he had decided to reverse an earlier decision to accept the Sheikh Zayed Book Award, for which he had been declared Cultural Personality of the Year 2021.

Earlier, Habermas accepted the Sheikh Zayed Book Award, one of the Arab World’s most prestigious and well-funded prizes, but then reversed the decision after reactions from the German media.

“I announced that I would accept this year’s Sheikh Zayed Book Award. It was a wrong decision, which I correct hereby,” he said in a statement shared with the Spiegel Online news website.

“I didn’t sufficiently make clear to myself the very close connection of the institution, which awards these prizes in Abu Dhabi, with the existing political system there,” he added.

The winner of each of the award’s eight categories receives the equivalent of $204,200.

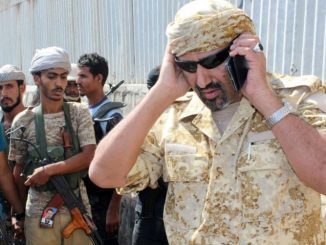

The award is named after Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, the late founder of the UAE and emir of Abu Dhabi.

Following Habermas’ announcement, the award put out a statement expressing its disappointment.

Though the UAE has often tried to cultivate a liberal, cosmopolitan image abroad, critics say the country ruthlessly represses dissidents.

The Gulf state has been accused of employing extrajudicial methods to crack down on dissent within its borders and has been repeatedly criticized for its human rights record.

The Amnesty International report of 2016 said that forced disappearances were pervasive in the country. However, the international rights group said the Emirati authorities continued to ban political opposition and to detain prisoners for such opposition.

Scores of Emiratis continued to serve prison sentences in the UAE-94 case, a mass trial of 94 defendants that concluded in 2013 with 69 convicted on charges of seeking to change the system of government.

Over two dozen prisoners of conscience, including well-known human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor, continued to be detained in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The state continued to restrict freedom of expression, taking measures to silence citizens and residents who expressed critical opinions on COVID-19 and other social and political issues.

A number of detainees remained in prison past the completion of their sentences without legal justification. A UK court found that head of government Mohammed bin Rashed Al Maktoum had abducted and detained two of his daughters.

At least 10 people continued to be arbitrarily detained after completing their prison sentences. Articles 40 and 48 of the counter-terrorism law (Federal Act No. 7 of 2014) stated that those “adopting extremist or terrorist thought” may be held indefinitely in prison for “counselling”. Most such prisoners were held at al-Razin prison in the desert south-east of Abu Dhabi city.

They included Omran Ali al-Harithi, a defendant in the UAE-94 trial, who should have been released in July 2019; and Abdullah Ebrahim al-Helu, convicted in June 2016 of belonging to the charitable arm of al-Islah, the formerly legal Emirati branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, who was due for release in May 2017.

The authorities released some prisoners after they appeared in videos posted to pro-government social media channels in which they “confessed” that al-Islah was a “terrorist” organization and repudiated their affiliation with it.

In March, the UK High Court of Justice (Family Division) made public a fact-finding judgement reached the previous December that concluded that the head of government had arranged for his daughter Shamsa’s enforced removal from the UK in 2000 and the “capture” and detention of another daughter, Latifa, in a maritime assault launched when she attempted to escape the royal family in 2018.

More than 25 prisoners of conscience remained in jail on account of their peaceful political criticism. They included attorneys Mohamed al-Roken and Mohammed al-Mansoori, former heads of the UAE Jurists Association (which the government took over in 2011 after the Association called for free national elections), who were convicted in the UAE-94 trial; Nasser bin Ghaith, a lecturer in economics at Sorbonne University’s Abu Dhabi branch, detained since 2015; and human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor.

Government agencies in Dubai and Ajman warned that they would prosecute individuals who spread information about COVID-19 deemed misleading by authorities, later announcing they had initiated several such prosecutions.

Emiratis and foreign national residents continued to face imprisonment following unfair trials. On 17 February, the State Security Chamber of the Federal Supreme Court upheld the conviction and sentencing of five Lebanese men on charges of planning violent acts in the UAE.

They had faced unfair trial procedures, including incommunicado detention for months, denial of access to lawyers, and use of coerced “confessions” as evidence.1 In May, Abdallah Awadh al-Shamsi – an Omani national born to an Emirati mother and an Omani father resident in the UAE – was sentenced to life in prison after proceedings marred by a similar pattern of violations.

The estimated 20,000-100,000 stateless people born in the UAE continued to be deprived of equal access to rights covered for Emirati citizens at state expense, such as state-subsidized health care, housing and higher education, or jobs in the public sector.

Access was dependent on proof of citizenship and stateless people were denied recognition as citizens, despite most of them having roots in the UAE going back generations.

Stateless Emiratis given Comorian passports under a 2008 deal between Comoros and the UAE found it difficult or impossible to get these passports renewed, leaving many of them, once again, lacking basic identity documents.

The UAE courts continued to issue new death sentences, primarily against foreign nationals for violent crimes. No executions were reported.