A report published by an independent online newspaper has narrated the full story of the Sisi regime’s targeting of Juhayna Food Industries, a leading Egypt-based manufacturer specialized in the production, processing and packaging of dairy, juice, and cooking products, for being “increasingly wary of demands for ever larger donations and cooperation in state-led projects” rather than any other allegations.

Mada Masr, Egypt’s leading independent, liberal online newspaper, has published a report titled, “Milking Juhayna for all it’s worth”, addressing the crisis of the giant a producer of milk, yogurt and juices, Juhayna Food Industries, after being targeted by the regime for differences on donations to the Tahya Masr Fund, a black-box reserve that is managed directly by Abdel Fattah al-Sisi without parliamentary oversight and is tax exempt, although Safwan Thabet who founded the company in 1983 donated LE50 million, roughly US$6.9 million in 2014. However, the regime wanted “ever larger donations and cooperation in state-led projects”, according to Mada Masr report:

In 1987 Juhayna, a producer of milk, yogurt and juices, launched an advertisement campaign to promote the distribution of its first cardboard milk cartons, marked with the now-iconic logo of a cow holding a wildflower in its mouth.

In its more than three decades of operation, Juhayna has transformed the juice and dairy industry in Egypt. The company expanded again this year, adding plant-based milk to the more than 200 products the food manufacturing giant exports to European, Arab and African countries.

Safwan Thabet founded the company in 1983 upon returning to Egypt from Saudi Arabia. The name is an ode to his mother’s hometown, Arab Juhayna, a Nile Delta village in Qalyubiya.

Thabet served as Juhayna’s chief executive and chairman until he resigned in January, five months after he was arrested on terrorism-related charges.

It is a stark reversal for a figure who sat among about a dozen other select businessmen at a 2014 iftar hosted by President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to discuss ways to support the national economy. The assembled businessmen eventually donated LE5 billion to the Tahya Masr Fund, a black-box reserve that is managed directly by the president without parliamentary oversight and is tax exempt. Thabet’s contribution came in at LE50 million, roughly US$6.9 million at the time.

Thabet’s donations to the Tahya Masr Fund continued for a time, but then Thabet lost his standing as a “patriotic businessman.” What happened? Mada Masr spoke to businessmen as well as political and legal sources informed of the crisis around the Thabet family to understand what led up to the Juhayna chairman’s arrest. What emerges is a picture not of a company harboring Brotherhood assets, as some rumors would suggest, and more of one increasingly wary of demands for ever larger donations and cooperation in state-led projects.

The fallout began on August 20, 2015, when the committee tasked with surveying and managing the assets of the Muslim Brotherhood decided to freeze Thabet’s assets under the pretext that he was a “member” of the Brotherhood, rather than being a mere “sympathizer” or “having relatives in the now-banned group as is being claimed.” According to the committee, investigations proved his support to the Brotherhood’s protests in the aftermath of June 30, 2013, and the Rabea and Nahda sit-ins.

In February 2016, the committee also froze 7.2 percent of Juhayna’s shares that Thabet owned indirectly.

When Juhayna initially went public 2010, Thabet’s family — he, his wife and his three children — owned 51.2 percent of the company’s shares via direct ownership or indirect ownership through SBSMH Investments Limited, which the family also owns, while the remaining 48.8 percent were owned by a number of Egyptian and other Arab investors.

After going public, Pharon Investments Ltd., in which the Thabet family holds a 72 percent majority stake, acquired 50.8 percent of Juhayna’s shares. The remaining Juhayna shares were bought by old and new investors.

The asset freeze leveled against Juhayna in 2017 was not the end of measures taken against Thabet. In January 2017, he was listed on the state’s terrorism list for a period of three years alongside 1,533 other defendants facing charges ranging from financing terrorist groups and monopolizing markets with the purpose of harming the national economy.

Despite being named on the terrorism list, Thabet was not arrested until December 2, 2020. After his detention by a security entity for four days, the State Security Prosecution ordered his remand detention for 15 days pending investigations in Case 85/2020 on charges of financing terrorist activities and joining an illegal group.

Two months later Seif Thabet, Safwan’s eldest son who was appointed CEO after his father’s detention, was also arrested and charged in the same case. While all of the other defendants in the case were held in Tora Farm Prison at the Tora Prison Complex, Seif’s whereabouts remained unknown from the time of his arrest in early February until at least April 23, according to his mother Bahira al-Shawy, who took to social media to say that she had been prevented from seeing her husband Safwan several times after being allowed to visit him once.

The other defendants in the case, many of whom are Muslim Brotherhood members, are allowed only one monthly visit — less than the weekly visits to which prisoners are normally entitled — at Tora Farm Prison, Brotherhood lawyer Abdel Moneim Abdel Maqsoud tells Mada Masr.

Hours after Seif’s arrest, security officials detained two Morsi-era ministers — former Transport Minister Hatem Abdel Latif and former Manpower Minister Khaled al-Azhary — alongside Sayed al-Swerky, the owner of Al-Tawheed wel Nour, a department store franchise. The three men were included in the same case as Thabet.

Following the arrests of the Thabets, Swerky, Azhary and Abdel Latif, rumors began to spread that the arrests were linked to the detention of Mahmoud Ezzat, the interim Supreme Guide of the Muslim Brotherhood last August from the Cairo suberb of the Fifth Settlement. These rumors were also conveyed to Mada Masr by a political source, who says that Ezzat gave authorities information on the group’s private investments and all businessmen who are either active or inactive Brotherhood members.

According to the story being told, the political source says, Juhayna’s name was brought up in what Ezzat described as one of the companies in which Brotherhood members invest their private assets. While Ezzat mentioned several names, the story goes, Thabet was the only one arrested, the source says.

However, a lawyer of one of the defendants in the case, who spoke to Mada Masr on condition of anonymity, impugned the validity of this retelling of events, arguing that security bodies are behind this rumor. For the lawyer, the businessmen come in various stripes — some are Brotherhood, and some aren’t — and they are facing the standard package of charges for anyone who runs afoul of the state.

Abdel Maqsoud, who has been present during Ezzat’s interrogations before the State Security Prosecution, says that prosecutors have not asked about Safwan Thabet during the official handling of the case. However, the Brotherhood lawyer says he “cannot with certainty know whether Ezzat was asked about Safwan Thabet during his detention by the National Security Agency before he was presented officially to the State Security Prosecution.” Abdel Maqsoud adds that he has not been allowed a private conversation with Ezzat since his arrest.

In the three decades that Juhayna and Thabet have been prominent figures, there has been no talk of a potential link between the businessman and the Islamist organization. However, Thabet’s mother is Khalida Hassan al-Houdaiby, the daughter of the second supreme guide of the Muslim Brotherhood, and the sibling of Maamoun al-Houdaiby, the sixth supreme guide of the group.

“Safwan is a businessman, but his family relations were never part of the story. The security agencies know and have followed him since he came back to Egypt. All his work was happening under the close eye of these agencies,” a prominent Egyptian businessman tells Mada Masr. “Safwan was like all of us. When the state asked for something, he did it. He has always been like this: before and after the January revolution, and before and after Morsi.”

Another businessman described Thabet as being at a significant distance from the Muslim Brotherhood and their social and political project in general.

According to Thabet’s own words in a 2017 book he wrote on his experience in the manufacturing sector in Egypt, he went straight to former Interior Minister Hassan al-Alfy upon his return in 1983 from Saudi Arabia, where he worked for years after his graduation from the Mechanical Engineering Department at Helwan University. Thabet writes that he told Alfy that he wanted to resettle in Egypt to work and invest and informed him directly that his maternal grandfather is Hassan al-Houdaiby, his maternal uncle is Maamoun al-Houdaiby, and his paternal uncle is the Armed Forces Major General Ahmed Thabet, who was the supply minister during the 1973 October War. According to Thabet’s narration, Alfy’s response was that “Houdaiby’s children live and work in Egypt freely because they have no business with politics.”

The book was published as part of a series titled “Businessmen of the good old time” by Arab Media Group publishers, where Mubarak aide, chair of the Senate Economic and Financial Committee and Bibliotheca Alexandria Director Mostafa al-Fiqqi serves as vice chairman.

During the 1980s and the 1990s and up until the January 25 revolution, Thabet’s business flourished. Former President Hosni Mubarak visited his factories more than once, and he forged close relationships with ministers of economy, finance and supply, to name a few. In 2013, he was elected to the head of the Food Industries Chamber of the Federation of Egyptian Industries for a four-year term.

When Sisi ascended to power, Thabet was invited to attend one of the first meetings with businessmen that the new president held in 2014, when Thabet announced he would donate LE50 million to Tahya Masr Fund.

Although Thabet’s and his family’s assets were frozen in 2015, he maintained a good working relationship with the state. Over the next four years, the state singled out Juhayna as one of top100 Egyptian companies. Thabet attended a ceremony that was hosted by then-International Cooperation Minister Sahar Nasr. During the ceremony, Thabet gave remarks appropriate for a power-appeasing businessman, saying that his company’s operations and plans are designed in alignment with the state’s 2030 vision.

In 2018, Seif signed an agreement for Juhayna to donate LE15 million to the Tahya Masr Fund as a contribution to the national campaign to end hepatitis C in Egypt. In appreciation for the contribution, the Armed Forces Finance Authority and the Tahya Masr Fund secretary, General Mohamed Amin Ibrahim, awarded the company an honorary shield, according to a press release by the company in June 2018. In addition, Thabet participated in initiatives and events in cooperation with several ministries, including contributing to a Health Ministry-led initiative to provide protective equipment to medical staff during the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Prior to the arrest of Thabet and his son, the family had participated every year in fairs organized and sponsored by the Supply Ministry to sell household goods at discounted prices, including the Ahlan Madares and Ahlan Ramadan commodities fairs, in which low-cost school supplies and food items for Ramadan meals are available, respectively.

Weeks before Thabet’s arrest, one of the senior officials tasked with overseeing new state-led milk production projects conducted several visits to one of Juhayna’s factories. During these visits, this official was allowed in on the how-to of managing the factory and the modernization of its equipment and operation systems, a second political source tells Mada Masr.

According to this source, Thabet appears to have been approached with a proposal to think about merging some of Juhayna’s factories with the new state-led initiative as a gesture of real support to food industries. Thabet treated this talk as mere chat rather than a request, the source says.

These visits coincided with Sisi’s repeated directives from last May and until early September to the prime minister, the agriculture minister and a number of other officials including Major General Mostafa Amin, the director of the Armed Forces National Service Products Organization, to establish a comprehensive integrated production and collection system all over the country. The plan included 200 milk collection centers.

Sisi drove these points home once again in remarks made just hours before Thabet’s arrest, calling on the government to take up the LE50,000 cost required to acquire international accreditation for each center.

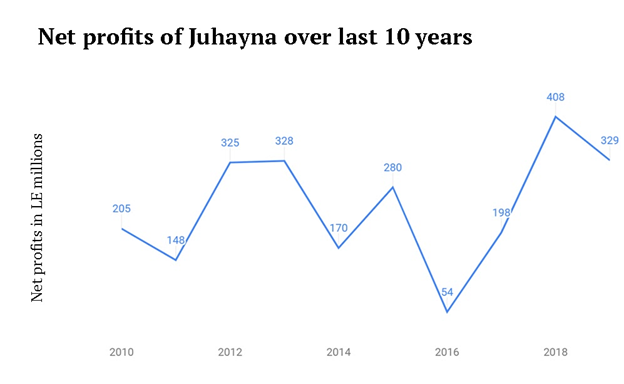

The visits also coincided with a period of record profits for Juhayna, which has survived severe shocks, including the energy price hike in 2014 and the devaluation of the Egyptian pound in 2016.

This graph below shows the development of Juhayna’s profits over a period of 10 years:

In addition to the strength of Juhayna’s brand, the company’s strong market position is directly linked to its excellent distribution capacities compared to its competitors. The company has more than 1,200 transportation trucks, according to a report issued by EFG Hermes in early 2019, and has now around 33 distribution centers delivering products to more than 65,000 outlets in 26 governorates, according to the company’s official website.

This robust logistical network has come under state scrutiny in recent weeks. On Monday, Reuters reported that Juhayna submitted formal complaints against traffic procedures that included revoking the licenses for a number of the company’s transport vehicles, describing the procedures as “incomprehensible and unjustified” and explaining that they may cause losses.

In letters seen by Reuters, the company said that the traffic administration and traffic investigation department in Giza are stationed “almost continuously at the company’s factories and the product loading sidewalks in the factories and branches.” The company stressed that these authorities withdrew the licenses for vehicles transporting dairy products, including 94 sales cars and 12 trucks, in addition to 26 heavy trucks belonging to outside contractors.

Juhayna submitted complaints to the ministries of trade, industry and supply, the chamber of food industries in the Federation of Egyptian Industries and to the attorney general of the 6th of October prosecution office.

These hindrances notwithstanding, Juhayna and the dairy manufacturing industry at large has room for even further growth, according to the EFG Hermes report. Only 45 percent of the total milk consumed by Egyptians comes from dairy factories like the ones Juhayna operates, and the average consumption of milk, juice and yogurt is relatively low on a per capita basis. Individual consumption is prone to increase, according to Hermes.

Another source from the public food manufacturing sector says that “the discontent against Thabet” came to a head not during the milk factory visits, but earlier — when he turned down a proposal from one of the ministers to purchase the struggling state-owned food manufacturing companies: Qaha and Edfina. “Thabet’s lack of interest in the proposal did not only stem from his lack of interest in the project,” the source says, “but also because of the big financial ask and the cash that his company would have to pay for the two companies.”

Earlier this month, Supply Minister Aly Moseilhy called on businessmen to purchase shares in Qaha and Edfina after both companies’ structure was converted into a shareholder-based one. “Please, come be partners with us,” Moseilhy said.

According to a source well informed of the case’s developments, Thabet and his family have been pressured since his arrest to give up their shares in Pharons Ltd. Co. The situation is no longer about money. “What is wanted is the assets, not the cash,” says the source.

Youm7 newspaper, a privately owned outlet known for reflecting the state’s thinking and security policies, stated explicitly that the state is required to intervene in order to “save” Juhayna from its founders. One of the Youm7 articles on the case ran a headline that read “Saving Juhayna comes after expelling Thabet’s family, bringing Juhayna’s management under state custody.”

Mada Masr made several attempts to solicit comments from the Thabet family on the reasons for the arrest of Safwan and Seif. However, the family emphasized that it would not comment on the matter and had instructed their lawyers to also refrain from making any public remarks out of fear that Seif and Safwan would face retaliation. All they hoped for, the family said, was for the continued safety of father and son while in detention. The family added that there may be a way out of the crisis via some sort of settlement.

A third political source said there are currently “proposals” on the table by “mediators” seeking a logical end to the crisis. “The continuation of this issue is in no one’s best interest. It does not make any sense that the state was honoring people who are financing terrorism. Safwan and his son received honorary awards. It is also against common sense that the state did not know who was investing his money and where, especially if we are talking about the Muslim Brotherhood. Furthermore, it is not in the state’s best interest to have talk of asset freezes of businessmen under various pretexts, which gives a negative impression about its intervention in the economy,” the source says.

The state’s move to arrest and freeze the assets of the Thabets, Swery and several other businessmen is indicative of a wider failure of the legal and judicial mechanisms used to lay hands on the assets of prominent businessmen, according to a judicial source close to the committee tasked with surveying and managing Brotherhood assets. This failure is in large part due to measures taken by businessmen to distribute their wealth to people close to them or in companies in which they indirectly hold a controlling share, the source says, adding that security forces have responded to this fact by increasingly applying pressure on businessmen to try to extract as much money as they can through donations to the Tahya Masr Fund.

Despite the curtailment of its distribution network, business at Juhayna’s factories is proceeding as usual under its new boss Mohamed al-Dogheim, Thabet’s Saudi partner. Meanwhile, the company’s more than 4,000 workers are following the news with concern that any show of sympathy could be used against them, one of the company’s employees who spoke to Mada Masr on condition of anonymity said in a brief conversation.

“It is not our business. We are here for bread only, and we do not know anything about the case and are not even asking. We are only scared about our source of income. Until now, things are going normally. We get our wages, and there is no problem. However, no one knows how this issue will end. It has been around for a while and is getting more complicated, while we are people who have responsibilities and do not want to be involved in this issue unjustly,” the work says.

Similar concern prevails outside of Juhayna’s factories. At Bahya Hospital for the Treatment of Breast Cancer, which has benefited from large Juhayna donations, there are those who feel anxious that the continuation of the crisis may jeopardize the food company’s pledge to build a larger Bahya facility in the low-income Giza district of Haram that would double the number of patients receiving free treatment and end long waitlists.