Egypt has a sharp shortage in physicians despite thousands of medical students graduating annually, mainly due to immigration of physicians from the country.

Egypt is facing an unprecedented wave of immigration by physicians, which raises suspicions over the quality of the situation of health care in the country, likely leading to further deterioration.

Egyptian physicians immigrate to seek better work and financial incentives. However, a retention policy needs to be developed to prevent Egyptian physicians from immigrating and quitting the country.

In fact, immigration of physicians has become a global phenomenon with significant implications for the healthcare delivery systems worldwide.

According to government statistics, around 7,200 new physicians graduate every academic year, but less than 50% actually register and practice, while many of them plan to quit the country.

The motivations and factors driving physician’s immigration are complex and continuously evolving. Over the past years, tens of thousands of physicians have reportedly left the country, leaving behind a remarkable shortage of physicians.

In addition to the low salaries and benefits, the high rate of deaths among Egypt’s medical workers during the outbreak of Covid-19 was a key driver for immigration of physicians. According to the official Egyptian Medical Syndicate, hundreds doctors have passed away from COVID-19.

According to some recent studies, the immigration of physicians results from a specific weighting of push and pull factors. Push factors are considered to be more important than pull factors, where factors related to professional development play a leading role.

On social media groups gathering people who intend to travel to Germany and the US, several users post opportunities and scholarships for doctors, medical technicians, and nurses.

These grab the attention of hundreds of Egyptian medical students and doctors. Among these users is Mostafa, an orthopaedic specialist, who is currently finishing his last year of the compulsory government internship where fresh graduates have to work/train in public hospitals.

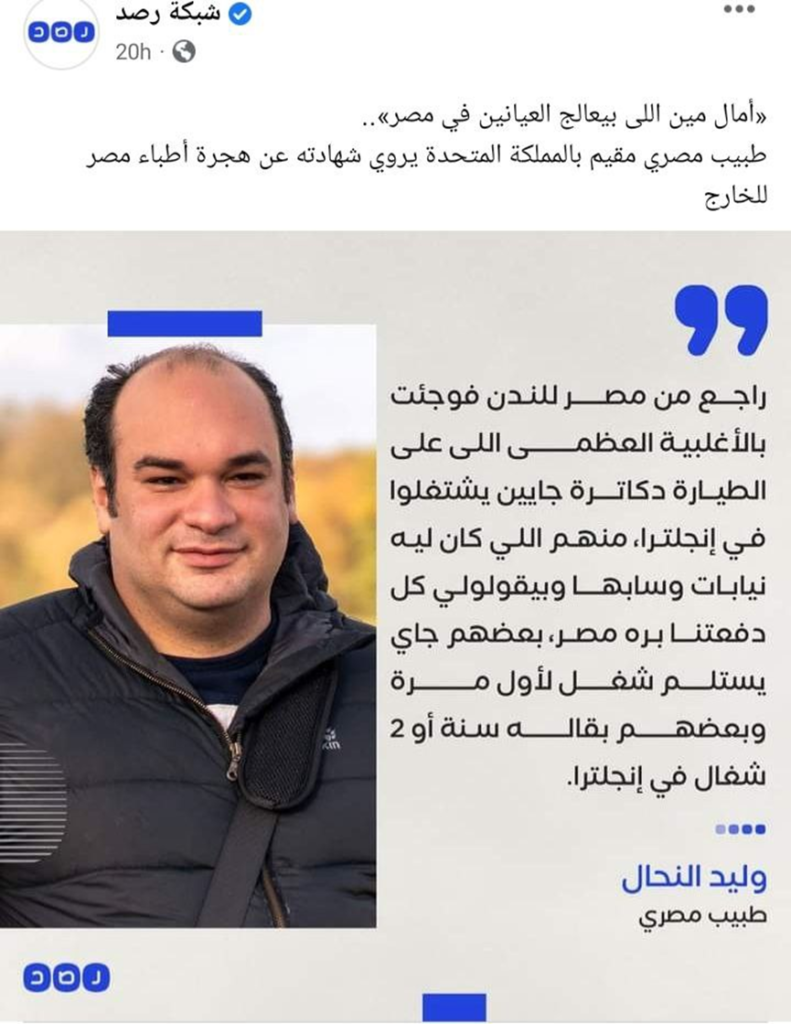

On its official page on Facebook, Rassd News Network published a post, reading: “So, who is treating patients in Egypt? An Egyptian physician residing and working in the United Kingdom narrates his witness about immigration of Egyptian physicians.” Rassd quoted Dr. Walid Al-Nahal, an Egyptian physician residing and working in England, as saying:

“Returning from Egypt to London, I was surprised by the fact that the vast majority of passengers on board the plane were Egyptian physicians coming to work in England, leaving behind all connections with everything in Egypt.. Some are getting work in London for the first time and others have been working there for a year or two.”

Egypt represents a lower-middle income country in the Middle East. Since 2011, the Egyptian sociopolitical situation has been shaped by a wave of political instabilities related to the Arab Spring uprising, which further escalated after the 2013 military coup. Egypt suffers from a shortage of physicians although an average of 10,000 medical students graduates annually from 24 public and 3 private medical schools.

The shortage in physicians is attributed mainly to the immigration of both qualified trainers and graduates due to low job satisfaction, and a search for better training opportunities. In 2016 alone, the density of physicians was estimated to be 1 physician per 12,285 inhabitants. The immigration of physicians abroad contributes substantially to the physician shortage in Egypt, a loss that cannot be replaced by recruitment of health care personnel from Sudan or Rwanda.

Common destination choices for Egyptian physicians include Gulf countries, Australia and the European Union (EU).

“Doctors’ immigration is worrying and threatens the collapse of the already neglected health system,” said Ehab el-Tahir, a member of the Medical Syndicate Council. He said an increasing number of doctors are resigning from public medical institutions, potentially emptying out some specialties of physicians.

“If this continues, Egyptian patients will soon find nobody to treat them,” he said.

The physician shortage was confirmed by Hala Zayed, the former minister of health, in a speech before Egypt’s parliament, where she said that there are 103,000 doctors for 100 million citizens, or 10 doctors per 10,000 citizens. The global average is 32 doctors for every 10,000 citizens.

There are many reasons discouraging physicians (or doctors as a common word used in Egypt) from practicing in Egypt. These include low salaries and undesirable working conditions, including poor medical facilities and a lack of supplies in government hospitals.

In addition, doctors say they need laws to protect them from patients and their families when they become belligerent if the doctors can’t successfully treat them or if the patients don’t like some aspect of their medical care.

“We, as doctors, have many problems, starting with the poor salaries, frequent insults, abuse by patients and their families, the distortion of our image and continuous accusations of negligence,” said Khaled Samir, a professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Ain Shams University’s Faculty of Medicine. “All of this drives many of us to emigrate.”

Doctors say that if a patient’s condition gets worse or if a patient dies, even if the doctor is not at fault, patients and their families can refer them to public prosecutors and the doctors can be subjected to the provisions of the criminal code. Doctors get an injury allowance for such circumstances but it is only 19 Egyptian pounds ($1.13) a month.

A newly graduated doctor earns about 2,000 Egyptian pounds, or $120, a month, while a specialist who has an additional degree gets about 3,000 Egyptian pounds, or $180.

The average monthly spending on all expenditures for an Egyptian family was about 3,058 pounds, or $183, in 2015, according to the latest figures available from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. (Those numbers were recorded before the devaluation of the Egyptian pound in 2016, and since then life has become much more costly for Egyptians paid in pounds.)

“I never regret my resignation from working in Egypt,” said Mustafa Abdel-Rahim, a pediatrician who now works in Kuwait. “The salaries are low, so the doctor works in clinics and private centers for 72 hours to meet his living and family needs, not to mention the lack of safety at work.”

Ahmed Refaat, a professor at Assiut University’s South Egypt Cancer Institute, agrees with Abdel-Rahim regarding the poor compensation for doctors and the lack of support for their role.

“A professor at the Faculty of Medicine does not get more than 10,000 Egyptian pounds ($600), while a specialist in any Arab country earns ten times that salary,” he said. “And those who leave the country will never think of coming back.”

Those doctors who stay in Egypt often leave critical but stressful specialties such as general surgery, intensive care, anesthesia, emergency and heart surgery and move to specialties with easier hours and higher income, such as plastic surgery, gynecology or pediatrics.

This trend has resulted in a large deficit in certain specialties and surpluses of doctors in other fields. For example, the National Heart Institute recently announced it needed to appoint 50 doctors in anesthesia and 30 doctors in cardiac surgery. But only one doctor has applied for each of those departments.

“There is a severe shortage in the specialties of emergency medicine and intensive care, because doctors prefer to travel abroad, in addition to the lack of a law to evaluate medical errors, leaving doctors exposed to nonspecialized criminal trials,” said el-Tahir, the member of the Medical Syndicate Council.

Egypt suffers from a shortage of physicians despite thousands of medical students graduating annually. In 2016, the density of physicians was estimated to be 1 physician per 12 285 inhabitants.

Immigration of physicians intensifies physician shortages in Egypt and the loss cannot be replaced by recruitment. Despite being a major supplier of immigrant medical graduates, yet only little is known about the pattern of physician immigration and its associated factors, which needs further study.