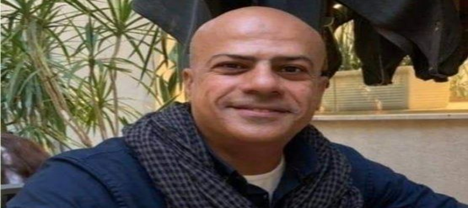

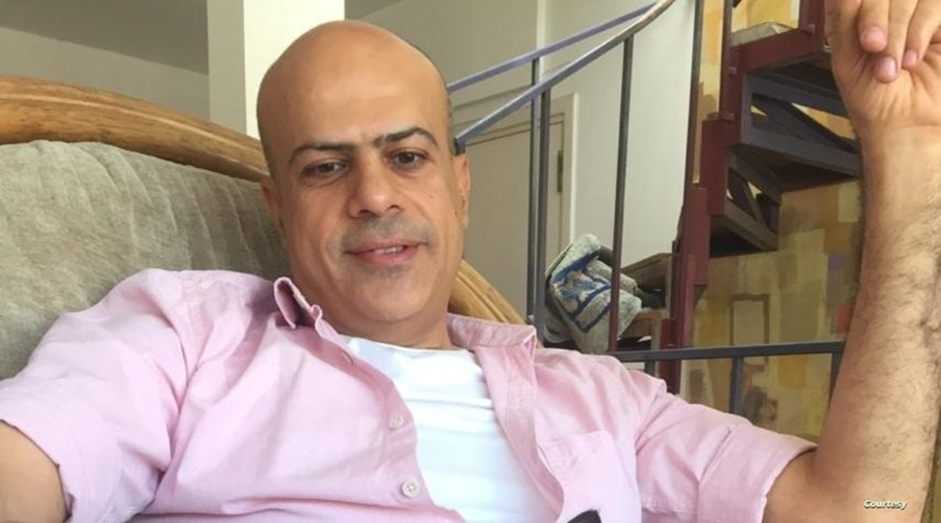

Newly obtained photos of the body of Egyptian economist Ayman Hadhoud, who died in custody strongly suggest that he was exposed to severe torture which ultimately led to his death in a psychiatric hospital.

Rights groups and the family of the economic researcher and government critic Ayman Hadhoud had called for investigation into his ‘suspicious’ death in custody

The leaked photos of the corpse of Egyptian economic researcher Ayman Hadhoud suggest he was tortured before his death, contrary to official claims.

Photos of Ayman Hadhoud’s body that were taken after his death in state custody and obtained by the New York Times (NYT), the Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN); as well others obtained by the Middle East Eye (MEE) strongly suggest torture or ill-treatment, as confirmed by forensic pathologists.

According to the New York Times, photographs of Hadhoud’s body, taken in the morgue of the psychiatric hospital where he died and obtained by The New York Times, showed injuries to his upper body, including what forensic experts said was possibly blunt force trauma, as well as burns on his face and head. Omar Hadhoud said his brother’s skull appeared to be fractured.

Also, DAWN obtained several previously unpublished photos of Hadhoud’s body, showing wounds, bruising, and discoloration to his face, head, and arms, where DAWN verified that these photos were taken at the hospital morgue on April 12, after which Hadhoud’s family removed his body.

DAWN shared these photos with a forensic pathologist who confirmed that Ayman’s face and forearms contain marks that natural processes do not explain and instead represent injuries inflicted on him.

Amnesty International first reported on the strong likelihood that Hadhoud was tortured before his death, using a separate set of leaked photos assessed by forensic pathologist Derrick Pounder.

Also, according to a report published by the Middle East Eye (MEE), the London-based news website has obtained post-autopsy photos of the corpse of Hadhoud, the 48-year-old senior economist and politician who was found dead at a Cairo hospital two months after his detention and disappearance.

Ayman Hadhoud, a well-known liberal economist and critic of the government, was researching corruption before he disappeared under mysterious circumstances.

Photos of Hadhoud’s body that were taken after his death in state custody strongly suggest torture or ill-treatment, as confirmed by forensic pathologists.

Ayman Hadhoud, a well-known liberal economist in Egypt, was researching some politically delicate topics like the military’s role in the economy before he disappeared into the custody of the country’s security forces in early February. He had regularly criticized the government and its economic policies on Facebook.

A month after he disappeared, he died suddenly under mysterious circumstances while in custody. But officials did not inform his family that he had died until more than a month after the March 5 date on his death certificate and claimed it was from natural causes, quickly clearing themselves of any wrongdoing.

“These are lies,” said Omar Hadhoud, Hadhoud’s elder brother, who collected his body from the morgue and said he saw signs of abuse. “It’s very clear his head was broken. Why else would they hide him?”

Photographs of his brother’s body, taken in the morgue of the psychiatric hospital where he died and obtained by The New York Times, showed injuries to his upper body, including what forensic experts said was possibly blunt force trauma, as well as burns on his face and head. Omar Hadhoud said his brother’s skull appeared to be fractured.

Another person who saw the body in the morgue and witnessed the photographs being taken said they, too, noticed visible injuries, patches of discolored skin and small brownish-red spots around his face and head. The person asked not to be named for fear of government repercussions.

The photographs raised suspicions that Hadhoud, 48, was abused before his death. His family and human rights groups are now calling for a full, independent investigation.

Egypt’s Interior Ministry and head prosecutor, which almost never acknowledge wrongdoing in such cases, have insisted that their own quick investigation conclusively found that the death was caused by a “sharp drop in blood circulation and cardiac arrest” and possibly a Covid-19 infection, adding that the authorities bore no responsibility.

The government has refused to comment beyond the Interior Ministry and prosecution statements.

Egypt’s police and security agencies have a long record of detaining, abusing and torturing their own citizens, especially those whom the government considers political opponents. The country’s human rights record has drawn considerable international scrutiny, condemnation and repercussions, with the United States withholding $130 million from its annual aid package to Egypt this year.

Previously, the emergence of evidence of abuses by the Egyptian security services has sometimes set off domestic protests or international tensions — including a police killing that helped ignite the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings and the discovery, in 2016, of the mutilated body of an Italian doctoral student, Giulio Regeni.

Anwar Sadat, a former member of Parliament who leads the Reform and Development Party, which Hadhoud belonged to and had advised on economic policy, dismissed the authorities’ explanations as “the usual answers which don’t satisfy anyone.”

Sadat is the nephew of the former president whose name he shares. He called for an investigation into Egypt’s mental hospitals and the more than monthlong gap between the date on Hadhoud’s death certificate and its official acknowledgment.

“There are too many question marks,” he said.

Hadhoud’s case prompted comparisons with that of Regeni, who disappeared while conducting research on trade unions in Egypt and whose body was found, riddled with marks of torture.

“This is happening over and over again in Egypt,” said Ayman Nour, a prominent opposition leader who is living in exile and was Hadhoud’s friend. “Anyone in Egypt is vulnerable to such practices.”

Hadhoud, a researcher who grew up in a poor neighborhood of Cairo and studied at the American University in Cairo on a scholarship, had been working on several politically delicate topics in the year before his death, his brother said. They included what he described as bribery by members of Parliament and how the military had come to dominate Egypt’s economy, suppressing private-sector competition and garnering revenues for itself at the expense of the country’s budget.

The Egyptian authorities frequently detain people for speaking out on social media or for conducting politically charged research.

“He believed someone should break the barrier of silence,” Omar Hadhoud said, adding that friends and family had repeatedly warned his brother that his research was dangerous.

“There were no red lines to Ayman. And he paid for this with his life.”

Hadhoud’s family first noticed him missing on Feb. 6, Omar Hadhoud said, when he failed to come home.

In statements on April 10 and April 12, the authorities claimed that Ayman Hadhoud had been caught trying to break into an apartment in Zamalek, an upscale Cairo neighborhood, the night he went missing. But he was never charged with a crime.

An April 12 statement by prosecutors asserted that he had schizophrenia, showing “poor concentration and attention, persecutory delusions, delusions of grandeur” and “raving incomprehensibly.”

But Hadhoud’s brother and acquaintances said he had never been mentally ill.

On Feb. 8, two days after he disappeared, the family learned where he had been taken when Egypt’s state security agency informed them that he was in their custody and summoned another brother for questioning about Mr. Hadhoud’s activities, work and family, Omar Hadhoud said.

But by then, according to the prosecutors’ April 12 statement, officers had already moved Hadhoud to the Abbasiya Mental Health Hospital in Cairo. Though the family asked repeatedly for his whereabouts and visited several government offices in person, they were not told that he had been sent to the hospital, Omar Hadhoud said.

They eventually heard through friends with contacts in Egypt’s health care system that he was at Abbasiya. When family members went repeatedly to the hospital, however, hospital staff either denied that Hadhoud was there or said that they would need written permission from prosecutors to visit, his brother said.

Not until April 9 did the authorities officially acknowledge that Hadhoud was hospitalized, when a police officer told the family to come collect his body. But his death certificate, which his brother provided, said that he had died more than a month before, on March 5.

The authorities have offered no explanation for the discrepancy.

“Without an independent, impartial investigation, Ayman’s family will never know the truth about his disappearance or his death,” said John Hursh, a program director for Democracy for the Arab World Now, a U.S.-based human rights group, which obtained the same photographs independently.

When Omar Hadhoud arrived at the hospital on April 10, he said he was at first told he could take his brother’s body for burial the same day. But then he was told that the authorities had suddenly ordered an autopsy for a few days later.

The photographs of Mr. Hadhoud’s body were taken after the autopsy. But Omar Hadhoud and another person who saw the body before the autopsy said that they saw the injuries and that they were not caused by the autopsy.

Four forensic experts who reviewed the photographs, which were taken surreptitiously, cautioned that they were not high-resolution and showed only part of Mr. Hadhoud’s body. Two said they could not draw definitive conclusions about how he was injured.

But most of them agreed that the photographs showed injuries to his upper body that could have been caused by beatings and burnings.

Dr. Karen Kelly, a medical examiner and associate professor of pathology at East Carolina University, said the photographs appeared to show that before he died, Mr. Hadhoud had received multiple small burns to his face, possibly from cigarettes, and might have received a blow to his face as well.

“Something happened to him prior to his death — possibly, probably torture,” she said. “I am concerned that it was torture.”

She also said that what appeared to be a relatively small incision in Mr. Hadhoud’s chest in the post-autopsy photographs indicated that only a partial, incomplete autopsy had been conducted, one that would not have detected evidence of beating on his back or other internal injuries.

Members of his family, as well as an independent expert, were barred from observing the autopsy, Omar Hadhoud said.

So far, the authorities have refused their requests to turn over the autopsy report.

Also, an Egyptian medicolegal expert told the Middle East Eye that the photos it obtained strongly suggest he might have a fracture in the nose and head, along with signs of beatings on his left shoulder and signs of burns on the face and his right forearm.

“CT scans need to be conducted to investigate where there are fractures in the skull,” the expert told MEE.

Hussein Bayoumi, Egypt researcher at Amnesty International, said the rights group assessed the same photos of his corpse, which suggests that Hadhoud was tortured or otherwise ill-treated before his death.

In a detailed analysis of the reported photos, forensic expert Derrick Pounder told Amnesty that “the marks to the face and forearms cannot be accounted for by the natural processes which occur after death (putrefecation) – they represent injuries.”

“The distribution of these marks strongly suggests repeated systematic infliction in life, that is to say ill-treatment/torture. The depressed appearance of the injuries and their distribution to the forearms and face suggests that they were more likely caused by burns rather than blows,” he added.

The family and their lawyer have not been allowed to receive a full copy of the autopsy report, according to Bayoumi.

The analysis matches statements by a family member who previously told MEE that prior to the autopsy, he saw Hadhoud’s body at the hospital with signs of beatings and torture. According to the relative, when the family took pictures of Hadhoud as proof of the wounds, hospital staff threatened not to release the body unless they deleted the photos.

Hadhoud, a senior economic adviser to Egypt’s liberal Reform and Development Party, was detained on 5 February and forcibly disappeared until 9 April, when his family was asked to collect his dead body from the Abbasiya Mental Health Hospital.

The Public Prosecution has insisted that Hadhoud died on 5 March of “hypotensive shock and cardiac arrest”, following its investigation of the case and an autopsy of the body. The investigation, based on the autopsy report, concluded on 18 April ruling out criminal reasons for the death and saying it was “not suspicious”.

However, the death of Hadhoud has been described as “suspicious” by a group of Egyptian and international rights groups, who reject the Public Prosecution’s conclusion that he died of natural causes.

This conclusion was rejected by the family and human rights organisations, who accused the National Security Agency (NSA), Public Prosecution and Abbasiya Mental Health Hospital of concealing the truth behind Hadhoud’s detention and death.

“Evidence indicates criminal violations behind Ayman’s death, as he was alive on the evening of 6 February when he was arrested on charges of alleged theft,” nine rights groups said in a report.

The issue of torture in Egypt came under international spotlight when an Italian parliamentary panel accused the Egyptian security apparatus of the kidnapping, torture and murder of Italian student Giulio Regeni in Cairo in 2016. A post-mortem examination showed he had been tortured before his death.

Regeni was among hundreds of other cases of deaths in detention that took place since President Sisi led a military coup against his democratically elected predecessor Mohamed Morsi in 2013.

Most of those deaths, as documented by the Geneva-based rights group Committee for Justice, were due to medical negligence, torture and poor detention conditions.

In the first 11 months of 2021, Egypt’s Nadeem Centre for the Rehabilitation of Torture Victims documented 93 incidents of torture in police detention, along with 54 deaths in police custody.

Human rights organizations have documented systematic torture of detainees in Egyptian security facilities, police stations, and prisons, and noted the frequent use of torture in instances of enforced disappearances, such as Hadhoud’s. Since Sisi came to power through a military coup in 2013, more than 1,000 detainees and prisoners have died within Egyptian detention facilities or prisons. This total includes at least nine minors and four people before Hadhoud already this year.