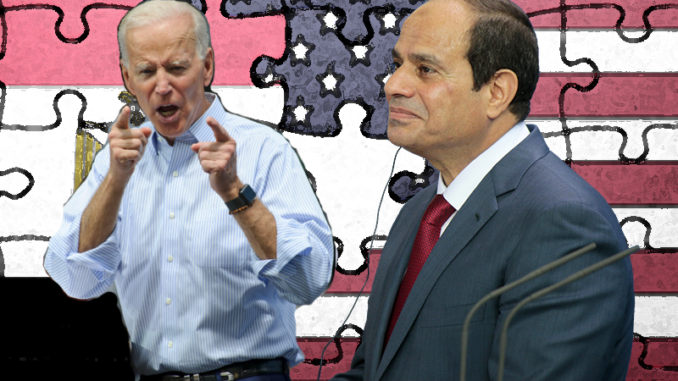

The White House has announced that U.S. President Joe Biden will travel to Egypt on 11 November to attend Cop27 in Sharm El Sheikh, the same day Egyptian authorities are aggressively trying to prevent a protest from happening.

However, human rights organizations expect that Biden should publicly call on Sisi’s government to protect the right of Egyptians to protest.

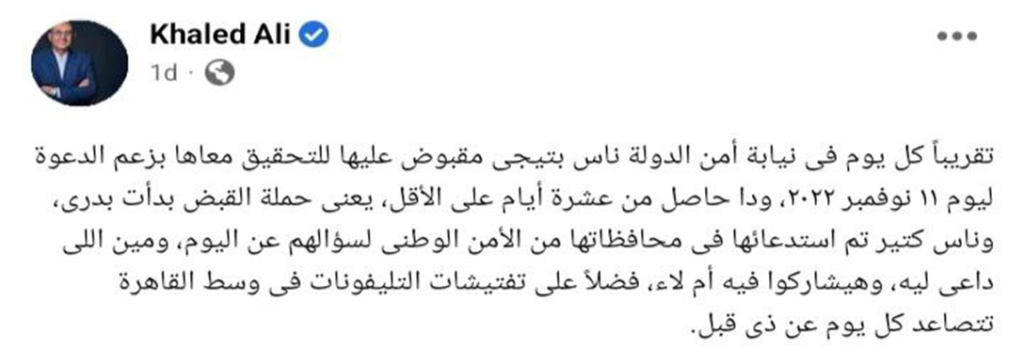

For the past 10 days, many people have been arrested and taken to State Security prosecution on suspicion of calling for protests on 11/11. Some others have been summoned and questioned by the National Security Agency about who is behind protest calls, whether taking part, and others, accoeding to lawyer Khaled Ali, Sharif Kouddous said in a tweet.

This is addition to ramping up police campaign of stopping people in downtown Cairo to go through their phones looking for political content.

The White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre on 28 issued a statement on President Biden’s travel to North Africa and Asia as well as Vice President Harris’s travel to Asia.

“President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. will visit Egypt, Cambodia, and Indonesia. On November 11th, President Biden will attend the 27th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27) in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt,” the statement read.

“At COP27, he will build on the significant work the United States has undertaken to advance the global climate fight and help the most vulnerable build resilience to climate impacts, and he will highlight the need for the world to act in this decisive decade.”

“COP27 will be held in Egypt—a nation highly vulnerable to climate change but antagonistic toward an essential stakeholder in the climate conversation: independent civil society,” states Sahar Aziz, Law professor, in a piece on Time magazine, titled, Egypt Isn’t Qualified to Host COP27.

“COP27 should be an opportunity for Egypt to lead by example; instead, hosting the event seems to be political cover for its self-defeating repression of civil society,” Dr. Aziz wrote.

Climate change has no regard for state borders. Nor does a nation’s wealth or power immunize it from the annual rise in temperatures exacerbating extreme flooding, droughts, and storms.

This reality is bringing together nearly 200 nations for COP27, to be held in Egypt—a nation highly vulnerable to climate change but antagonistic toward an essential stakeholder in the climate conversation: independent civil society. Indeed, the Egyptian government has given summit access only to local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that support the regime.

“With only 3.4% of its land arable and more than 30% of its population living in poverty, Egypt cannot afford contractions to its domestic food and water supply,” she stated.

Rising temperatures, water scarcity, and soil salinity are shrinking crop yields in the Nile Delta, which account for nearly all the nation’s domestic food supply, 11% of gross domestic product, and 21% of its labor force.”

Egypt has failed to fully address climate realities, and stymied Indigenous voices calling for more progressive approaches to the changing environment. COP27 should be an opportunity for Egypt to lead by example; instead, hosting the event seems to be political cover for its self-defeating repression of civil society.

Since coming to power in a military coup he led against the country’s democratically elected president Morsi in 2013, Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, the head of the Egyptian regime has treated civil society as enemies of the state. NGOs that refuse to support government policies have had their assets frozen, leaders arrested, and activities surveilled by security forces. Some civil-society leaders have been kidnapped and tortured.

Environmental activists are among those targeted by the state’s crackdown on dissent. A recent report by Human Rights Watch found, for example, that when environmental groups opposed the government’s reintroduction of coal in cement factories, campaign supporters were summoned by the state security forces, harassed at airports, or threatened with terrorism-related charges.

An Egyptian law passed in 2019 restricts NGOs from conducting opinion polls or field research without government approval.

In the rare case when approval is granted, the NGO can’t publish results without further government blessing. Nor can civil society cooperate with foreign organizations or receive foreign funding without prior government assent—rarely given.

Further, the government can at any point declare illegal any activity that undermines “national security, public order, or public morals”—based on opaque, unilateral criteria.

Civil-society organizations that fail to follow the law are subject to fines or dissolution. Their leaders are arrested and charged with trumped-up terrorism charges while their personal assets are frozen, all without due process.

Moreover, the Egyptian government has blocked more than 500 websites and severely restricted access to information and reporting on human rights and environmental issues.

Debates that implicate industrial pollution, as well as corporate interests in real estate, tourism development, and agribusiness that exacerbate the impacts of climate change, are politically off-limits.

The consequence is an absence of climate activism and public awareness about the grave environmental challenges facing Egypt. Field research, data collection, and policy recommendations by independent experts are vetted by government security forces whose priority is preserving the regime—not saving Egypt from natural disasters.

The stakes of climate change are too high for this punitive approach to an engaged, independent civil society.

“Widespread hunger and water shortages are potent ingredients for civil unrest and revolution—the very thing the Egyptian government wants to prevent. COP27 should be a wake-up call for autocratic regimes across the world that the effects of climate change will end their rule long before any real or imagined political opposition,” Aziz concludes.

“A recent report by Human Rights Watch found … that when environmental groups opposed the Egyptian govt’s reintroduction of coal in cement factories, campaign supporters were summoned by the state security forces, harassed at airports, or threatened with terrorism-related charges,” commented Amy W. Hawthorne, human rights defender and researcher.

Activists and NGOs are redoubling efforts to call attention to the dire human rights conditions under which the next UN climate summit will be held, stressing that there can be no climate justice without political freedoms.

Starting 6 November, thousands of people from across the world will begin to descend on the Egyptian seaside city of Sharm El Sheikh to attend the UN climate change conference (COP27). Among them will be political leaders, experts, representatives of large business and non-governmental organisations, activists and journalists who will gather to discuss global climate action for two weeks at the most important climate forum of the year.

As COP27 draws near, activists and human rights organisations are redoubling their efforts to bring to the world’s attention the dire human rights conditions under which the climate summit will be held. Adamant that these are interconnected struggles, they are stressing that there can be no climate justice without political freedoms, open civic space and respect for human rights.

For nearly a decade now, Egyptian authorities have carried out relentless crackdowns on civil society, imposed draconian restrictions and systematically muted critical voices – according to investigaations by human rights organisations. Along the way, they have curtailed the ability of Egyptian environmental groups – which are still largely in their infancy – to carry out their work, while not directly outlawing or expelling them.

Egyptian and international activists and human rights groups have provided numerous reasons as to why climate justice and political freedoms should be addressed simultaneously. One of them, largely practical, is that without an open public space that allows for everything from a free press to popular organisation and social mobilisation it will not be possible to push for the research, analysis, progress and radical changes needed to tackle the climate crisis.

Mona Seif, an Egyptian activist and Abdelfattah’s sister, recently wrote that the reality that most of those participating in COP27 are choosing to ignore is that in countries like Egypt the “true allies, the ones who actually give a damn about the planet’s future, are those languishing in prisons.”

“Restrictions on civil society in general and independent environmental voices is a clear impediment to the climate policies that countries and the world needs,” Pearshouse of Human Rights Watch said.

“Egypt, as the host country, has [led a] crackdown on independent environmental voices and as a consequence of that it’s incredibly difficult to have conversations around Egypt’s expansion of fossil fuels inside the country, for example,” he noted.

Starting 6 November, thousands of people from across the world will begin to descend on the Egyptian seaside city of Sharm El Sheikh to attend the UN climate change conference (COP27).

Rhetorically, a lot of countries have nodded to the fact that there is a connection between respect for human rights and climate policies that we all need.