A misguided effort to integrate Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) into the Sudanese Armed Forces led to a tragic but predictable conflict, states Foreign Policy.

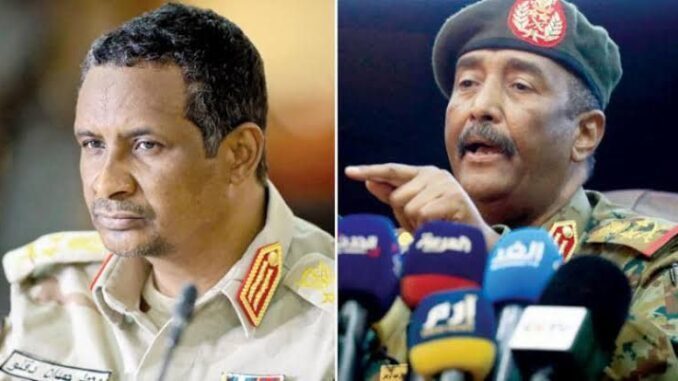

“Fighting in Sudan began on April 15 after years of tension between the country’s two power brokers: Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the country’s de facto leader and head of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, widely known as Hemeti, who leads the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Running street battles started in Khartoum and spread across the country. Residents report that low-flying airplanes strafe the ground. Reports of horrendous human rights violations are starting to emerge,” states Justin Lynch, a researcher and analyst, in a recent analysis published by Foreign Policy, continuing as follows:

Fighting in Darfur resulted in the deaths of three aid workers with the World Food Programme. Markets in Darfur have reportedly been burned down. United Nations and NGO compounds have been invaded and looted across the country. The European Union’s ambassador to Khartoum was assaulted in his home by soldiers.

Sudan is facing a state collapse similar to Yemen’s. The SAF launched an intense bombing campaign in Khartoum and may soon take the upper hand in the capital thanks to their superior air power. The air force has been a decisive element in Sudan’s wars, especially beginning in 2003, when the SAF and the precursor to the RSF, the janjaweed, fought on the same side during the war in Darfur.

The power of Sudan’s air force is why RSF operations in the early hours of the conflict focused on taking control of airports across the country so SAF air operations would be grounded. It has only partially worked. However, it may take weeks to dislodge the RSF from residential buildings in Khartoum that they have converted into military installations. At the same time, it will be difficult to defeat the RSF in their tribal homeland of Darfur, especially with their ability to mobilize soldiers from neighboring Chad. Sudan’s descent into a full-scale civil war appears more likely by the hour.

What may emerge out of a civil war is a conflict that also sucks in the entire region and some global powers. Egyptian soldiers who were training with the SAF were arrested by the RSF in the early hours of the conflict. Diplomats fear that Cairo may be preparing to support the SAF. There are reports of tribal mobilization along the border of Chad and Sudan, the traditional homeland of Hemeti. At least part of the RSF’s information operation has been based in the United Arab Emirates.

The UAE has been a key ally for Hemeti during the former’s war in Libya and Yemen. The UAE also benefits from financial ties to Hemeti’s businesses. Global Witness reports that the UAE has also been a key supplier of military equipment to the RSF. Russian Wagner Group mercenaries trained RSF troops and had officials stationed inside some of their bases. To halt the conflict, the leaders of South Sudan, Djibouti, and Kenya have offered to mediate.

Perhaps the only powers that have a limited ability to shape events in Sudan are the United States and its Western allies. To try to prevent the bleak outlook of state disintegration in Sudan, the U.S. government is working with Arab states—namely Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—but these U.S. allies are on opposing sides in Sudan. However, Western diplomats have told me they understand that a return to the pre-April 15 status quo is becoming increasingly unlikely as the fighting continues. The absence of U.S. influence comes just four years after a high point for Washington’s hopes in Sudan.

Months of protests in early 2019 led to a military coup against former dictator Omar al-Bashir. It appeared that three decades of U.S. policy to support democracy could finally bear fruit. But the United States and other Western nations pressured civilian protesters and the military to form a transitional government. The eventual transitional constitution meant that elections were scheduled to take place in 2022.

If there was a moment when hope for democracy was lost in Sudan, it was when this transitional constitution was agreed to. The military was allowed to run the country for the first part of the transition. “We still have not achieved what we are fighting for,” Sara Abdelgalil, then a spokesperson for the Sudanese Professionals Association, which helped organize the protests, told Foreign Policy in 2019. “Omar al-Bashir is not there, but the regime itself is still there. Objective one has not been achieved. Objective two has not been achieved, which is a civilian government. It’s like having a diversion in the middle of your journey.”

Burhan was the head of state and was trusted with following through on his promise of democracy.

Immediately when the transitional period began, it was apparent that Western hopes for democracy were far-fetched.

I interviewed the new civilian prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok, in a house that was given to him by a prominent Sudanese family because Burhan and the military initially refused to even give him a place to stay. The core elements of Sudan’s protest movement in 2019, Sudan’s labor unions, lost power due to infighting. Civilian political parties squabbled over power. Reforms that Hamdok wanted to make were blocked by Burhan and Hemeti. The illusion of any civilian authority ended in 2021, when Hamdok was removed in a military coup. The military’s promise to hand over power to civilians proved hollow. The U.S.-backed transition revealed itself as fundamentally flawed.

Perhaps the greatest example of U.S. delusions was Washington’s insistence on calling Sudan’s transition “civilian-led.” There was nothing about Sudan’s transition that was civilian-led. The 2019 transitional constitution laid out that the military would lead for the first 21 months of the transition, followed by civilians for the next 18 months.

Although Hamdok was a civilian prime minister, it was a mostly powerless job. Still, the U.S. government insisted on this phrase, even when the military handover date to civilians was repeatedly delayed. U.S. officials told me that they knew the term was more aspirational than descriptive. But the linguistic acrobatics Washington employed suggested officials believed that they could simply call Sudan a democracy and it would become one.

It’s not clear if the U.S. or Western governments could have prevented the 2021 coup against Hamdok. The transitional constitution that was backed by the United States was a bad deal. However, the ensuing U.S. and Western policies in Sudan directly contributed to the violence that we see today. It is a story of Western peacebuilding and its limits.

Sudan’s feuding generals bear primary responsibility for the current fighting in Sudan. But the precipitating event of the current war in Sudan was a reconciliation agreement and security sector reform plan that was pushed by the United States and the U.N. mission in Sudan. Immediately after the coup against Hamdok, the United States and the U.N. revitalized the plan. It meant returning to a version of the failed 2019 constitution and trusting the military leaders to keep their promises.

The basic idea of the security sector reform was to unify the SAF and RSF into a single army. It is difficult to estimate each force’s size. The SAF have around 100,000 soldiers, while the RSF have a smaller standing army of anywhere between 30,000 and 50,000 fighters but a large reserve force because they can mobilize tribal allies.

Negotiations were held for months trying to get the two sides to agree on a path forward. The problem was that neither Burhan nor Hemeti wanted to give up the power that he’d accrued. The plan became a pressure cooker. “It became a real shit show with all the participants being real amateurs,” a Western diplomat in Khartoum told me after one of the negotiation workshops between the SAF and RSF. “Diplomats here and headquarters think one-dimensionally.”

The outcome that we see of the plan was predictable, in part because it is a repeat of history. The peacemaking effort was a reproduction of agreements that were made in South Sudan in 2013 and 2016. Those also led to civil wars.

In his excellent book When Peace Kills Politics, Sharath Srinivasan details how international peacemaking in Sudan and South Sudan has contributed to these types of civil wars. “[P]eacemaking—because of how its ways of working inevitably collide with the politics of a civil war—can risk reproducing logics of violence,” he writes.

The security sector reform in Sudan, as it has elsewhere, created a competition that incentivized Hemeti and Burhan to build up their forces. It also meant that both men would have to be placed under civilian control, which was in neither’s interest. The generals publicly committed to reform and democracy, but it seems the only people who believed them were U.S. and U.N. officials.

Diplomats have told me that they face limited tools to stop the violence in Sudan. The United States and other nations are promoting a humanitarian cease-fire that allows civilians to seek safety and collect food, but it has not been fully honored so far. Putting pressure on Egypt and the UAE would be critical to avoid a regional conflict and to press for a humanitarian cease-fire so civilians can escape. An intense effort to evacuate U.S. citizens may come soon. But once the current crisis is over, there needs to be a reckoning that U.S. and Western policy has not only failed to bring democracy but contributed to Sudan’s collapse.

It’s not clear if Washington is ready. Once fighting began on April 15, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken repeated U.S. delusions on Sudan: “This is a real opportunity to finally carry forward the civilian-led transition.”