The Egyptian government has so far failed to show commitment to adopting and carrying out structural reform, a situation that warns of a lasting crisis looming.

The IMF is yet to agree a date with the government for a first review of its current loan agreement. We explore the government’s progress in implementing reforms and the outlook for the coming months, stated Victor Tricaud, a senior analyst of Control Risks, in a piece recently published, continuing as follows:

The IMF and other multilateral lenders will continue to put pressure on the authorities to implement structural reforms to put the economy on a more sustainable course.

Plans to privatise state-owned assets and reforms aimed at leveling the regulatory playing field between public and private entities will likely progress slowly over the coming months.

A dearth of investment will translate into a continued scarcity of foreign exchange and drive payment and contract risks as the state will increasingly be forced to review spending plans.

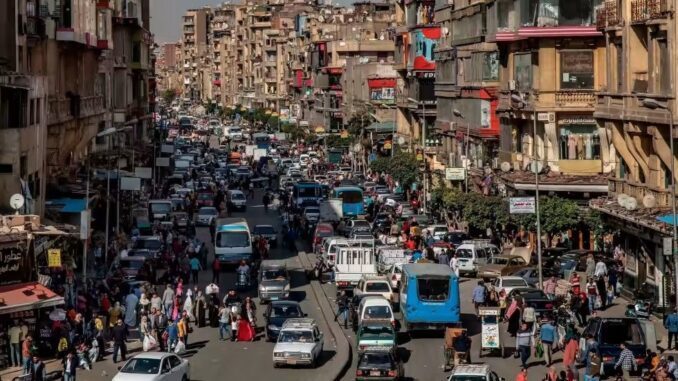

Meanwhile, high inflation will drive rising popular frustration, sustaining civil unrest threats despite the authorities’ repressive management of public opinion.

The IMF agreed the USD 3bn Extended Fund Facility (EFF) – its fourth loan program to Egypt in six years – in December 2022, with a view to disbursing the funds over 46 months.

The deal envisioned the first of eight periodic reviews taking place on 15 March. However, the review has yet to take place. The delay points to the IMF’s growing intent to put pressure on the government to implement reforms agreed as conditions for the EFF.

Among the agreed policy priorities are:

-A commitment to a freely floating exchange rate and monetary policy geared towards price stability and inflation reduction.

-Structural reforms aimed at leveling the playing field between state-owned enterprises, including military-owned entities, and the private sector.

-Fiscal policy tightening, including a review of tax exemptions to free zone entities and state-owned entities, and a reduction in fuel subsidies.

However, four months after the agreement was ironed out, the government is yet to demonstrate substantial progress on key objectives. After an initial devaluation on 4-11 January, the Egyptian pound (EGP, local currency) has remained largely stable despite widespread market anticipation of further devaluations.

Mid-May, the pound traded on the black market at EGP 37: USD 1 (against an official rate of EGP 31: USD 1). Meanwhile, financial derivatives used to hedge against currency risk price in further devaluations. The EGP 12-month non-deliverable forward (a currency-based forward contract) anticipates the exchange rate in a year to stand at approximately EGP 43: USD 1.

The authorities have made similarly little progress when it comes to privatisations. The IMF agreement mentions a USD 2.5bn target to be raised in a first phase of stake sales by the end of June 2023 (the government in late April revised this target to USD 2bn). However, only two sales have taken place to date raising just USD 147m.

The planned sales that have attracted most scrutiny – of military-owned oil product marketing company Wataniya and bottling company Safi – have so far failed to materialise. Concerningly, the assets of Wataniya appear to be in the process of being transferred to another military-owned company for which there are no stake sale plans.

Delays to the IMF’s first review will push back further disbursements under the EFF package, as well as discussions on a separate Resilience and Sustainability Facility that could see Egypt obtain an additional USD 1.3bn in financial support from the IMF. The delays will also likely further discourage other potential financial backers from extending support to Egypt.

Remarkably, even Cairo’s traditional backers in the Arabian Peninsula have shown limited interest in investing in Egyptian assets. These traditional backers have been put off by financial volatility and resulting disagreements over asset valuations.

The authorities will likely make moves in the coming months to demonstrate – at least nominally – their commitment to reforms. They will do so to ensure they secure additional IMF disbursements to meet spending needs and debt repayments, build up foreign exchange reserves, and avert further credit downgrades in the coming months.

Significantly, credit rating agency S&P on 21 April downgraded its credit outlook for Egypt’s sovereign debt from “stable” to “negative”. It also estimated total external funding needs through to June 2024 to stand at USD 37bn.

Another EGP devaluation, further limited stake sales in state-owned assets and some efforts to rationalise government spending therefore remain likely in the coming months.

However, in the absence of a strong signal of commitment to deep structural reform – or a “coherent story”, as Central Bank of Egypt Governor Hassan Abdullah put it on 14 April – investor sentiment will remain dampened.

As a result, acute pressure on the currency will persist over the coming year and foreign exchange will remain in short supply, sustaining sovereign risk.

As the government starts implementing limited measures to reduce spending, including on projects incurring high foreign currency costs, foreign contractors and suppliers will likely be pressured to accept contract renegotiations and extensions of project timelines.

Meanwhile, continued scarcity of foreign exchange in Egypt’s financial system will cause payment delays due to accessibility issues faced by private economic players and as domestic banks increasingly aim to protect their foreign exchange reserves. The IMF requires the central bank to closely monitor commercial banks’ foreign asset positions.

The persistent currency crisis will also sustain pressure on living conditions. The authorities will seek to shield the most vulnerable segments of society, including by increasing social spending. Nevertheless, double-digit inflation will continue to eat into Egyptians’ purchasing power for energy and food staples.

Although the government has been effective at containing popular discontent over the past decade, including when grievances are driven by economic factors, the upcoming presidential election in 2024 will likely crystallise frustration at economic mismanagement, particularly among young people.

Such dynamics will sustain potential for an increase in the scale and frequency of civil unrest – from the current relatively low base – in the coming months.